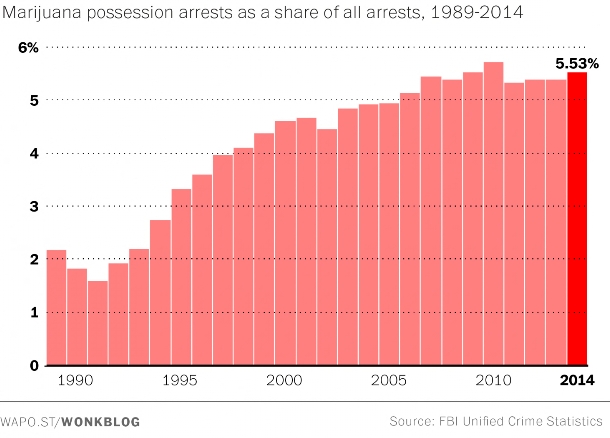

Marijuana Possession Arrests FBI Stats 1989-2014

WTF

WTF

43rd District Court Judge Robert Turner says it is one of the worst pieces of legislation he has ever seen. He made that assessment of the Michigan Medical Marijuana Act (MMA) back in June 2009 when dismissing pot growing charges brought by the Oakland County Prosecutor against Robert Lee Redden and Torey Alison Clark. Last week, the Michigan Court of Appeals affirmed Oakland Circuit Court Judge Martha Anderson’s reinstatement of the criminal charges against Redden and Clark. Now, the accused Madison Heights couple will either have to plead or go to trial. At the time of the raid on the couple’s residence, the Oakland County Sheriff seized 1.5 ounces of pot, some nominal cash, and about 21 small plants. Three weeks prior to the raid, each defendant had submitted to a medical certification exam with Dr. Eric Eisenbud (not making it up) of Colorado (and of the recently founded Hemp and Cannabis Foundation Medical Clinic) and applied for a medical marijuana card pursuant to the MMA. Their cards, however, had not been issued at the time of the raid. At the couple’s preliminary examination before Judge Turner, the prosecutor argued that: a) the defendants were required to abstain from “medicating” with marijuana while their applications to the State of Michigan’s Department of Community Health were pending; and b) the defendants did not have a bona fide physician-patient relationship with Dr. Eisenbud. Judge Turner indicated that the MMA was confusing relative to what constituted a reasonable amount of marijuana. The defendants in this case were found with an ounce and a half; the MMA allows 2.5 ounces. Judge Turner made the following ruling:

For that reason, I believe that section 8 entitles the defendants to a dismissal, even though they did not possess the valid medical card, because section 8 says if they can show the fact that a doctor believed that they were likely to receive a therapeutic benefit, and this doctor testified to that. And Dr. Eisenbud is a physician licensed by the State of Michigan. And that’s the only requirement that the statute has. You don’t have to be any type of physician, you just have to be a licensed physician by the State of Michigan.

So, based on that, I find section 8 does apply. And I believe I’m obligated to dismiss this matter based on section 8 of the statute.

Under the applicable court rules, the prosecutor appealed the district court dismissal to the Oakland Circuit Court. In reversing her district court counter-part, Judge Anderson held that Judge Turner improperly acted as a finder of fact in dismissing the case. Judge Anderson also questioned whether the couple could avail themselves of the MMA’s affirmative defenses at all, due to their purported failures to comply with the provisions of the act; i.e. keeping the pot segregated and locked-up, and waiting until they received their cards from the Department of Community Health prior to growing their pot. At the time of the Madison Heights bust, however, the couple could not have received marijuana cards because the DCH had not started issuing the cards. To date, almost 30,000 certifications have been issued. In their opinion last week affirming Judge Anderson, the Court of Appeals held that the MMA’s affirmative defenses were available to defendants even though they did not have their cards at the time their pot was confiscated. The Court of Appeals held against defendants, however, on the basis that, at the time of their preliminary examination in district court, their affirmative defense under the MMA was incomplete and thus created fact questions. The Court found the following fact issues to be unresolved at the conclusion of the exam: the bona fides of the physician-patient relationship; whether the amount of marijuana found in the residence was “reasonable” under the Act; and whether the marijuana was being used by defendants for palliative purposes, as required by the Act. The most interesting thing about the Court of Appeals’ Redden decision is the scathing concurring opinion of Judge Peter D. O’Connell. Judge O’Connell wrote separately because he would have more narrowly tailored the affirmative defenses available in the MMA, and because he wished to “elaborate” on some of the general discussion of the Act set forth in the briefs and at oral argument. Elaborate he did. Judge O’Connell’s 30-page opinion first notes that the possession, distribution and manufacture of marijuana remains a federal crime and further notes that Congress has expressly found the plant to have “no acceptable medical uses.” In what will undoubtedly become a classic line from his opinion, Judge O’Connell writes, “I will attempt to cut through the haze surrounding this legislation.” The judge is skeptical that folks are really using pot to “medicate” and suspects that they are using the plant for recreational purposes. He also takes note of the poor quality of the legislation to the extent that it conflicts with other provisions set forth in the Health Code. Judge O’Connell next takes a tour de force through the legislative history of the MMA. Here, we learn that the act was based on model legislation proposed by lobbyists known as the Marijuana Policy Project of Washington D.C. The group advances both the medicinal and recreational uses of marijuana. “Confusion”, and lots of it, is how Judge O’Connell views the MMA. In one of the many footnotes to his opinion, the Judge warns against all marijuana use until the score is settled, once and for all, by the Michigan Supreme Court:

Until our Supreme Court provides a final comprehensive interpretation of this act, it would be prudent for the citizens of this state to avoid all use of marijuana if they do not wish to risk violating state law. I again issue a stern warning to all: please do not attempt to interpret this act on your own. Reading this act is similar to participating in the Triwizard Tournament described in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire: the maze that is this statute is so complex that the final result will only be known once the Supreme Court has had an opportunity to review and remove the haze from this act.

Euan Abercrombie, 1st year student at the Hogwarts school would probably remark; “Wow”. For their part, the criminal defense bar, commenting via listserv, have basically gone wild over the concurring opinion, with its multiple web site references and pictures of marijuana advertisements. The consensus among the defense bar, however, is that the majority opinion is correct and that Judge Anderson, at the end of the day, got it right; Redden was not the cleanest case to dismiss under the Act. Finally, it seems that the Oakland County Sheriff and Prosecutor correctly anticipated last week’s Court of Appeals’ decision. A few weeks prior to the issuance of the Redden decision, they conducted a series of dispensary raids, ruffling tons of feathers along the way. For some preliminary guidance, we have prepared a legal guide for the MMA for those seeking to use marijuana for legitimate palliative purposes under the Act. Take note, however, that at least one appellate jurist would have folks managing chronic “pain” with prescription meds until the medical marijuana mess is sorted out by our Supreme Court.

Monday, September 20, 2010

April 2011 Update: As we’ve warned our readers, and as Judge O’Connell warned in his opinion, marijuana possession remains a federal crime. This week, the feds raided a warehouse-style dispensary in Commerce Township. The law enforcement action is covered in this article in the Oakland Press.

PONTIAC, Mich. – The Michigan appeals court is criticizing an Oakland County judge for sending a 70-year-old man to prison after he insisted he was too poor to make consistent payments to a crime victim.

Oakland County judge for sending a 70-year-old man to prison after he insisted he was too poor to make consistent payments to a crime victim.

In a 2-1 decision, the court said Judge Martha Anderson failed a key step: She yanked Ghazi Marji’s probation and sent him to prison in 2015 without trying to confirm that he was truthful about his weak finances. Marji, a former trucker, was 70 at the time.

The appeals court says the prosecutor and probation department never presented firm facts about Marji’s assets. Judge Elizabeth Gleicher says prosecutors need more than “smoke and mirrors” to lock up someone.

Marji had paid $8,000 toward $23,000 owed to an assault victim. He spent a year in prison.

(Pursuant to MCL 333.26426 (i) (1), (2), (3), (4) and (5) and Section 507 of Public Act 268 of 2016)

December 22, 2016

(l) The amount collected from the medical marihuana program application and renewal fees authorized in section 5 of the Michigan medical marihuana act, 2008 IL 1, MCL 333.26425.

$9,841,058.49

(m) The costs of administering the medical marihuana program under the Michigan medical marihuana act, 2008 IL 1, MCL 333.26421 to 333.26430.

$5,293,599.99

Donny Barnes said he just wants to be a regular guy.

He just wants to run his small businesses scattered around Oakland County. Just wants to hang out with his family at their split-level home on a woodsy street. And just wants to keep using medical marijuana for calming the neck and shoulder pain that Barnes said has plagued him ever since he was in a snowboarding accident at age 19.

But a drug bust in 2014 “turned my life upside down,” said Barnes, 41, of Orion Township. Police seized his property, shutting down his antique resale and spyware businesses, and charged him with possessing more than 100 pounds of marijuana, which Barnes and his lawyers argued didn’t belong to him.

This month, after two years of legal battles, Barnes’ lawyers claimed what they called a rare victory against the Oakland County Prosecutor’s Office, widely known for its aggressive prosecutions of medical-marijuana cases; and against the confiscatory tactics of OAKNET, the county’s much-feared Narcotics Enforcement Team.

Oakland Circuit Judge Denise Langford Morris dismissed a criminal charge against Barnes — marijuana possession with intent to distribute — and she ruled that police had failed to establish probable cause for raiding Barnes’ house, his office and warehouse.

Ecstatic at the ruling early this month, Barnes’ lawyers said it was a sign that times are changing — that a Michigan judge, even in such a conservative bastion as Oakland County, refused to continue waging the discredited war on drugs against one of Michigan’s medical marijuana users.

Yet, Oakland County law-enforcement officials said Barnes merely got lucky with a lenient judge and that, on appeal, the tables would be turned.

A county sheriff’s spokesman said that detectives had indisputable evidence of Barnes having been a big-time marijuana dealer, one who’d tried to hide his illegal activity under the cloak of medical marijuana while overseeing the sale of plastic baggies of marijuana to total strangers — a violation of the state law that allows “transfers” of the medicinal drug but only from a state-registered “caregiver” to that person’s five registered “patients.”

► Police seize property and cash in questionable raids

► Watchdog group gives Michigan a ‘D-‘ on forfeiture laws

► Cannabis industry roiled by White House comments on enforcement

The spokesman said that nothing about the ruling would change the tactics of Oakland County’s drug investigators. And the prosecutor’s office said it decided last week to appeal.

The outcome of the appeal could decide not only Barnes’ fate but also whether his case becomes a landmark ruling that aids others in similar circumstances.

The appeal of the case will explore just what constitutes a legal search and seizure of citizens in Michigan, who have faced civil forfeiture of their cars, cash and even their farmland and houses in some marijuana busts.

It will be argued in a year when Michigan could pivot toward more tolerance of the drug, or the state could adopt even tighter restraints under a Trump administration whose top law enforcer is the notoriously anti-marijuana Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

And the appeal will occur in a year that began with Gov. Rick Snyder signing a bill that gives limited protections to citizens facing civil forfeiture; they no longer must pay a bond of 10% of the value of their seized property to challenge the forfeiture in court. When Snyder signed the bill in early January, both sides of the political spectrum in Michigan — both the conservative/Libertarian Mackinac Center for Public Policy and the liberal American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan — called for more protections.

Outside Michigan, in 12 other states, law enforcement must get a criminal conviction before a suspect forfeits property, and in two states — New Mexico and Nebraska — civil forfeiture is altogether banned, Jarrett Skorup, spokesman for the Mackinac Center, said in the news release.

It was late November 2014 when police shook up what Barnes said was his tranquil lifestyle.

“They even took the Christmas presents I had wrapped for my kids,” Barnes said.

Heavily armed police in masks seized his family’s cars as well as the business computers, tools and considerable inventory of his several trades, and took the contents of several bank accounts including one belonging to his mother. That scenario is a familiar one around Michigan, and especially in Oakland County, where authorities are notorious among marijuana users for being merciless to those accused of skirting Michigan’s medical marijuana act.

Countless defendants in such cases, lacking the money to mount aggressive legal defenses, have been forced to plea bargain, to give up their possessions and accept jail or prison sentences as well as pay fines said David Moffitt a Bingham Farms lawyer.

One of two attorneys defending Barnes. Because his family “has significant resources,” Barnes was able to fight back and win the dismissal, Moffitt said.

This ruling “sends a strong message that in appropriate procedures on the part of police and prosecutors will result in dismissal. To have an Oakland County judge dismiss search warrants for faulty procedures is a game-changer in the state because everyone looks at Oakland County for their legal leadership on key issues.

“What this judge said was that you can’t just kick down doors and seize people’s property without having good reason to do so,” he said.

The same judge, after reviewing a lengthy brief submitted by Barnes’ attorneys, allowed him in a ruling last fall to use medical marijuana while out on bond “for a very demonstrable medical need,” instead of the opioid painkilling pills that caused him dangerous side effects, Moffitt said.

Getting a judge’s approval to use the drug as a bond condition is rare enough, but Moffitt said he was thrilled that Langford Morris wrote a detailed opinion justifying her circuit court ruling, making it precedent-setting for the state, he said.

One strikingly unfair tactic of Oakland County authorities is to arrest a medical-marijuana user, seize property “and then not even file charges if the defendant doesn’t contest the forfeiture — that’s become a standard approach there,” Moffitt added. Barnes wasn’t arrested until 14 months after the raids, seemingly not until he “aggressively challenged and contested the forfeiture case” in a civil case completely separate from his criminal case, his lawyer said.

“Both Mr. Barnes and I believe that the Oakland County sheriff’s department is protecting us every day, but I think they must agree that not everything they do is done perfectly in every case, and this is one of those cases,” said Moffitt, who is a former Oakland County commissioner from Farmington Hills.

Medical-marijuana cases can be complex, said Oakland County Undersheriff Mike McCabe. And so, there was nothing odd or unfair about how long detectives took to investigate before Barnes was arrested, he said. “With the sensitivity of these cases, the prosecutor goes over them with a fine-tooth comb” before approving arrest warrants, he said.

The sheriff’s and prosecutor’s offices have taken strong and specific issue with the dismissal of charges against Barnes. Among his small-business activities was a monthly free magazine called The Burn, whose masthead listed as publisher “Donald Barnes III.” Each edition was loaded with full-color ads, the most prominent ones being those for Metro Detroit Compassion Club, a facility open six days a week at the same address in Waterford Township as Barnes’ magazine

.

Among the come-ones for the Metro Detroit Compassion Club? “All meds locally grown … Providing our members only the best … We now accept valid out-of-state medical cards.”

That line refers to cards issued by numerous states, including Michigan, showing that someone is approved to use medical marijuana although not approved to buy medical cannabis from just anyone in Michigan except under the state’s tightly controlled system that ties caregivers to five so-called and only five “patients.”

So, when undercover informants of the Oakland County Sheriff’s Office were able to buy medical marijuana last year four times at the Metro Detroit Compassion Club, detectives linked that wrongdoing to Barnes, who was listed as the “resident agent” on the incorporation papers of the nonprofit club.

That’s when they decided to burst into the magazine’s offices, as well as into the compassion club at the same address where they found about two pounds of marijuana, and into a warehouse Barnes owned that was full of marijuana plants and more than 100 pounds of marijuana stored in refrigerators, as well as into Barnes’ rambling modern house that held about four pounds, McCabe said.

Did all of the marijuana belong to Barnes? If the case goes to trial, prosecutors will show that much of it did and the motive was to sell the drug for profit, McCabe said. At the warehouse, “the marijuana was in small baggies in refrigerators,” he said.

As for the nonprofit compassion club, it constituted a dispensary — a retail outlet for selling marijuana, McCabe said. Even though Detroit is said to have more than 100 dispensaries, operating mostly without interference by the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office, Oakland County authorities abide by the view of Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette, who has declared dispensaries illegal in Michigan.That will soon change, but it hasn’t yet, McCabe said.

Dispensaries are going to be legal in Michigan, through a new law enacted last year, “but not until at least early 2018 — that’s what we’ve been told by people in Lansing; that’s the soonest anybody can get a license to operate one,” McCabe said.

A top attorney at the Oakland County Prosecutor’s Office was adamant about not dropping Barnes’ case.

“We felt that the evidence rose to the level showing that Mr. Barnes was violating state law,” said Paul Walton, Oakland County’s chief assistant prosecutor.

The judge “made the statement that Mr. Barnes was simply an officer of the corporation, but there’s every reason to believe that he had significant involvement, if not outright ownership,” in the dispensary masquerading as a nonprofit club, Walton said.

So,was the ruling was a victory for medical-marijuana users across Michigan, as Barnes’ attorneys insist? Or just a temporary setback to the law-enforcement establishment in Oakland County, standard bearers for a rigid approach to users and distributors of medical marijuana?

Only time, and Michigan’s higher courts, will tell.

Contact Bill Laitner: blaitner@freepress.com