Sep 11, 2016 | Blog, Legalization, News

The Michigan Senate approved a surrogate to HB 4209 of 2015 by a vote of 25-12 which creates the Medical Marihuana Facilities Licensing Act. The bill is similar to the version that was overwhelmingly passed by House lawmakers in October, but does contain a number of changes. HB 4209 returns for a concurrence vote to the House and then to Governor Snyder.

MEDICAL MARIHUANA FACILITIES ACT AND MARIHUANA TRACKING ACT

- House Bill 4209 (passed by the House as H-5) Sponsor: Rep. Mike Callton, D.C.

- House Bill 4210 (passed by the House as H-2) Sponsor: Rep. Lisa Posthumus Lyons

- House Bill 4827 (passed by the House as H-1) Sponsor: Rep. Klint Kesto

- Committee: Judiciary Complete to 1-4-16

SUMMARY:

House Bill 4209 creates the Medical Marihuana Facilities Licensing Act to establish a licensing and regulation framework for medical marihuana growers, processors, secure transporters, provisioning centers, and safety compliance facilities. The regulatory framework created by the bill for marihuana draws on elements of the regulatory structure in place for alcohol under the Michigan Liquor Control Code and gaming under the Michigan Gaming Control and Revenue Act.

House Bill 4827 creates the Marihuana Tracking Act to require the establishment of a “seed-to-sale” system to track marihuana grown, processed, transferred, stored, or disposed of under the Medical Marihuana Facilities Licensing Act (House Bill 4209).

House Bills 4209 and 4827 are tie-barred to each other, meaning neither could take effect unless both are enacted.

House Bill 4210 amends the Michigan Medical Marihuana Act to, among other things, allow for the manufacture and use of marihuana-infused products by qualifying patients and manufacture and transfer of such products by primary caregivers to their patients.

All three bills would take effect 90 days after enactment.

BRIEF SUMMARY OF HB 4209:

The bill is tie-barred to the Marihuana Tracking Act (House Bill 4827). A brief summary of significant provisions of House Bill 4209 follows:

A state operating license, renewed annually, would be required to operate as a grower, processor, provisioning center, secure transporter, or safety compliance facility. The application process for licensure requires written approval of the applicant and of the marihuana facility location by the municipality (city, township, or village) in which the marihuana facility is to be located.

A municipality could enact an ordinance to authorize one or more types of marihuana facilities, and limit the number of each type of facility, within its boundaries; charge an annual local licensing fee up to $5,000; and enact other ordinances related to marihuana facilities such as zoning ordinances.

The Medical Marihuana Licensing Board would be created within the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA). The Board would have general responsibility for implementing the act and all powers necessary and proper to fully and effectively implement and administer the act.

Licensees, registered qualifying patients, and registered primary caregivers (hereinafter “patient” and “caregiver”) would receive specified protection from criminal or civil prosecutions or sanctions if they were in compliance with the act. “A registered qualifying patient” would include a visiting qualifying patient.

A tax rate of 3% would be imposed on the gross retail income of each provisioning center.

Rather than annual renewal license fees, an annual regulatory assessment would be imposed on licensees to pay for medical-marihuana-related services or expenses of certain state agencies.

Two new funds would be created to receive revenue from taxes, application fees, annual regulatory assessments, fines, and other charges.

Rules would be required to be promulgated as specified in the bill, including the establishment of maximum THC levels for medical edibles sold at provisioning centers and daily purchasing limits by patients and caregivers to ensure compliance with the Michigan Medical Marihuana Act.

Licensees would have to file annual financial statements, prepared by a certified public accountant, of their total operations.

A Marihuana Advisory Panel would be created within LARA to make recommendations concerning rules and the administration of the act.

BRIEF SUMMARY OF HOUSE BILL 4827:

Briefly, the bill would:

Require the system to track, among other things, lot and batch information throughout the chain of custody; all sales and refunds; plant, batch, and product destruction; inventory discrepancies; loss, theft, or diversion of products containing marihuana; and adverse patient responses.

Require the system to track patient purchase limits and flag purchases in excess of authorized limits.

Provide real-time access to the system to local law enforcement agencies, state agencies, and the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA).

Require operation of the system to comply with HIPAA and exempt information in the system from disclosure under FOIA.

Require licensees under the proposed Medical Marihuana Facilities Licensing Act (House Bill 4209) to supply LARA with tracking or testing information regarding each plant, product, package, batch, test, sale, or recall in or from the licensee’s possession or control. A provisioning center would have to include information identifying the patient to, or for whom, the sale was made and the primary caregiver, if applicable, to whom the sale was made.

Create penalties for a licensee who willfully fails to comply with the reporting requirements: a civil infraction

BRIEF SUMMARY OF HOUSE BILL 4210:

The bill would, among other things:

Revise the definitions of “medical use” and “usable marihuana” to include products using extracts and plant resins (known as “edibles”).

Define “marihuana-infused product” and “usable marihuana equivalent.”

Provide immunity to a qualifying patient or caregiver from arrest or prosecution or penalty for certain conduct.

Prohibit transporting or possessing a marihuana-infused product in a vehicle except as specified. Create a civil fine for a violation.

Prohibit using butane to separate resin from a marihuana plant in a residential structure.

Specify the bill is curative and the provisions retroactive.

Here’s the link to the Michigan Legislator website to see more details and future updates

House Bill 4209

House Bill 4827

House Bill 4210

Here’s an opposing POV

DETROIT NEWS

September 11, 2016

Sheriff: Medical marijuana bills may aid criminals

Lansing — Oakland County Sheriff Mike Bouchard is warning state lawmakers that a sweeping overhaul of Michigan’s medical marijuana law awaiting their final approval could lead to convicted drug dealers and murderers running pot shops.

Bouchard, a longtime opponent of the state’s medical cannabis law, has focused his criticism on language in a five-bill package that would prohibit felons with drug convictions from operating a licensed marijuana dispensary within a decade of their conviction of incarceration.

“If some guy who was a heroin dealer and killed his competitor and got released from prison, 10 years later he’s eligible to run a cash drug business, legally,” Bouchard said. “Obviously that’s fraught with peril.”

The legislation also would disqualify anyone with a misdemeanor conviction involving controlled substances, theft, dishonesty or fraud from obtaining a medical marijuana dispensary license until five years after the conviction.

“It doesn’t make sense to have conviction felons, including convicted murders, involved in a cash drug business,” Bouchard said.

Bouchard, a Republican and former state senator, said the Michigan House of Representatives should add restrictions barring drug felons from getting dispensary licenses or Gov. Rick Snyder should veto the package of bills, which the Michigan Senate approved Thursday.

Birmingham criminal defense attorney Bruce Leach, who specializes in defending medical marijuana patients, said Bouchard is engaging in “reefer madness fearmongering.”

“Law enforcement has a bias and self-interest in keeping marijuana illegal because they profit from arresting people and seizing their property through civil forfeiture proceedings,” Leach said.

The medical marijuana bills would make long-sought changes to the 2008 voter-approved law by creating a regulatory system and taxation of medical marijuana sold in licensed dispensaries.

The current law has been mired in conflicting legal interpretations for the past eight years, leading to a plethora of stores in cities like Detroit and Lansing selling cannabis to patients with state-issued medical marijuana cards.

State Sen. Rick Jones, chairman of the judiciary committee, defended the bills and said Bouchard’s criticism is “too little, too late” after he spent months crafting compromise legislation that law enforcement and prosecutors could live with.

“For Sheriff Bouchard to come at this late date and now claim he has a problem, I think is poor judgment,” said Jones, R-Grand Ledge. “He had plenty of opportunity to have input.”

Jones, a former Eaton County sheriff, said someone convicted of a drug offense 10 or more years ago should not be barred from working in a budding new industry.

“If somebody 10 years ago got picked up for (drug) possession, I certainly don’t think that should, 10 years later, preclude them from having employment,” he said.

The legislation would create a new Medical Marijuana Licensing Board that would be empowered to reject applicants if there were objections to their criminal background, Jones said.

“I don’t think that very many violent people are going to apply for a license,” he said.

Bouchard, a former state Senate majority floor leader, said the Legislature should treat medical marijuana dispensary licenses the same as other regulated industries that prohibit certain felons from employment.

“You can’t be a stock broker if you’ve got a felony conviction,” the sheriff said. “You would expect they would uphold the same standards they have for banking, gambling, for alcohol and for cigarettes.”

The package of bills needs a concurrence vote by the state House to go to Snyder’s desk for the governor’s consideration. The Republican governor has not said whether he would sign the bills.

But Lt. Gov. Brian Calley indicated Friday the Snyder administration is interested in having a regulatory system that ensures medical marijuana cultivated and sold to terminally ill patients is subject to inspections like fresh produce in supermarkets.

“That’s really the main crux behind it, that’s the thing that I think this bill advances,” Calley said in an interview on the Lansing radio station 1320 AM WILS.

The bills also would create a legal framework for communities to regulate where medical marijuana dispensaries are located, he said.

Calley urged sheriffs and law enforcement officials to “reach out” to House members with any “additional concerns or changes that need to be made” to the bills.

“Until it passes through the Legislature, it can still be modified,” Calley said. “So keep working on it.”

clivengood@detroitnews.com

Apr 21, 2016 | Legalization, News

Canada to introduce legislation in 2017 to legalize marijuana

OTTAWA — The Canadian government announced Wednesday that it will introduce legislation next year to decriminalize and legalize the sale of marijuana, making Canada the first G7 country to permit widespread use of the substance.

The announcement was made by Canada’s health minister, Jane Philpott, at a U.N. drug conference in New York. It follows through on a promise made during Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s successful election campaign last fall.

Philpott said details of the legislation are being worked out, but she vowed that the government “will keep marijuana out of the hands of children and profits out of the hands of criminals.”

With the Liberals holding a majority in the House of Commons, the marijuana legislation is likely to pass. The path toward the legalization of marijuana is the latest in a string of policy announcements from the 44-year-old Trudeau that have moved Canada to the left after a decade of Conservative Party rule, including last week’s unveiling of legislation to permit assisted suicide.

Trudeau, whose new government remains extremely popular, has long been associated with the marijuana legalization issue. While an opposition party member in Parliament, Trudeau admitted to occasional use of marijuana. “I think it’s five or six times that I’ve taken a puff. It’s not my thing,” he told reporters at the time.

The Conservative Party attempted to use that statement as proof that Trudeau was a political lightweight and a pothead. In the 2015 election, the Conservatives ran ads in ethnic newspapers falsely alleging that Trudeau backed the sale of marijuana to children.

The attack ads failed, in part because most Canadians no longer see the legalization of marijuana as a problem. A recent survey by Nanos Research, an Ottawa public opinion firm, showed that 68 percent of Canadians “support” or “somewhat support” legalizing marijuana and only 30 percent are opposed.

The population is more divided when it comes to allowing Canadians to grow marijuana at home, and about 50 percent of respondents said that they expect legalization to lead to more usage by those younger than 21.

Unlike in the United States, where marijuana regulation is shared by the states and the federal government, in Canada the issue falls almost solely under federal jurisdiction. Marijuana use has been expanding since a court ruling in 2000 allowed Canadians to possess and grow small amounts for medicinal reasons.

Full legalization will make pot available in a way similar to alcohol. That could encourage Americans, particularly those in border areas, to pop over for a puff or two.

Already, Ontario’s provincial premier, Kathleen Wynne, has volunteered that the provincially owned liquor monopoly would be happy to sell the drug. Canada’s major drugstore chains have said that they would like to get in on the business, too.

After several court rulings, commercial marijuana operations have sprouted across the country. Although currently limited to medicinal sales, the companies have been keenly anticipating legalization allowing for widespread use.

One study by a leading Canadian bank estimated that legalization could spark development of an annual marijuana trade worth about $10 billion Canadian (about $8 billion U.S.).

Brendan Kennedy, president of Privateer Holdings of Seattle, welcomed the Canadian announcement. His company owns Tilray, a medicinal marijuana facility in British Columbia, and he is looking to build a facility that would supply the market for recreational marijuana in Canada.

“The eyes of the world are on Canada as the medical marijuana program matures and the recreational program is being implemented,” he said in an interview. “Canada will be the first G7 country to have a national recreational program different from Alaska, Colorado, Oregon and Washington,” where state laws allowing marijuana use still bump up against U.S. federal prohibition.

There is still a series of negotiations required between the national government and the provinces to figure out regulation, taxation and distribution. Trudeau’s point man on the issue is Bill Blair, a former Toronto police chief.

Blair said marijuana should be treated like such intoxicants as alcohol. “We control who it’s sold to, when it’s sold and how it’s used. And organized crime doesn’t have the opportunity to profit from it.”

Original Post By Alan Freeman April 20 at 4:03 PM

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/canada-to-introduce-legislation-in-2017-to-legalize-sale-of-marijuana/2016/04/20/85d375a0-0715-11e6-bfed-ef65dff5970d_story.html

Apr 10, 2016 | Blog, Legalization, Michigan Medical Marijuana Act

Michigan’s medical marijuana law is a mess and dispensaries are popping up like, well, weeds and patients, police and politicians say something needs to change.

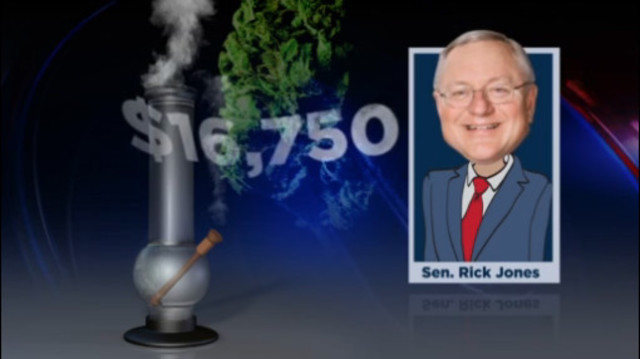

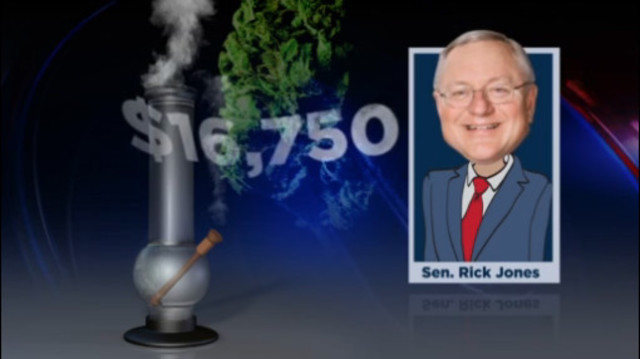

For the second year in a row, lawmakers are promising action in the meantime, FOX 2 found that their campaign accounts have reached new highs.

Local News

State lawmakers are finally poised to fix problems with Michigan’s medical marijuana law. It’s a worthy goal, one that that has proven very lucrative.

In fact, their efforts to help patients get better pot, has helped the politicians raise quite a lot.

M.L. Elrick: “How nice do you think it would be for the people of Michigan to say, ‘Here’s a guy who’s not going to take money because he thinks it’s might create at least the appearance of a conflict of interest?'”

Sen. Rick Jones (R-Grand Ledge): “Well … ”

That’s Rick Jones, chairman of Senate Judiciary Committee. Any effort to reform Michigan’s medical marijuana law will need Jones’ blessing.

Jones: “There’s probably a thousand factions out there.”

And many of them have given Jones’ campaign fund or his political action committee a big, fat check.

Jones: “I don’t choose who they donate to.”

That’s because lawmakers are trying to fix problems caused by the 2008 state referendum that made marijuana legal for medicinal purposes only, of course.

Voters approved using cannabis to treat the ill or aching, but questions have cropped up about the legality of matters like dispensaries and marijuana edibles and oils.

The state supreme court has weighed in on some matters, but law enforcement, law makers – and even law breakers – still have plenty of questions.

Key players in the reform efforts are the chairmen of the house and senate judiciary committees.

“What we have right now in Michigan is basically the wild, wild, west,” Jones said.

“We need to have some sort of structure for patient safety,” said Rep. Klint Kesto (R-Commerce) “For consumer safety, if it becomes legal, for a structure so that cities, townships, villages, counties are able to understand where the product is, where it’s going for taxation purposes, in order to provide the services that come after.”

“What this will do is license growers, it’ll license people who transport the product and it will license dispensaries,” Jones said. “People will know what they’re getting. It will be tested for all the bad things like the mold and the bug spray and all that to make sure that people aren’t getting that.

“Treating it more like a medicine I think is important.”

So in one of the ironies that is commonplace in the Capitol, Kesto, who is a former prosecutor, and Jones, a former sheriff, are spending a lot of time hanging out with people who make a living selling weed.

“It’s the American way of politics,” said Rich Robinson.

Still, even the cops say something must be done. Of course, no good deed goes unrewarded in Lansing.

And Kesto and Jones have collected plenty of campaign cash from folks who want to grow grass.

“It’s not surprising at all that the money’s coming out now,” said Robinson: “It’s directed with a purpose. It sure isn’t random.”

Robinson, of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network, has tracked the flow of dough in Lansing for years. He says lawmakers are experts at turning controversy into campaign checks.

“In the way this plays out, Sen. Jones will certainly consider the point of view of the interest group,” Robinson said. “But it’s ‘Step into the milking barn first before we have this conversation.'”

Campaign accounts for key Republican lawmakers have been getting fat with checks from all the folks with a stake in medical marijuana reform.

Jones leads the judiciary committee that is weighing potential changes to the rules. He recently raked in more than $16,000.

Rep. Mike Callton (R-Nashville) led an early house effort to change the law. Since then, he’s collected more than $12,000.

Rep. Kesto has also been a leader on the issue. he’s snagged more than $11,000.

As Senate Majority Floor Leader, Mike Kowall draws a lot of water. And he’s cashed checks worth more than $5,000.

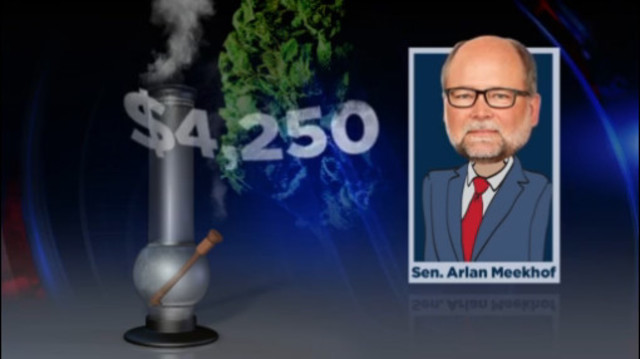

Senate Majority Leader Arlan Meekhof knows how to count votes, too. And the amount sent to his political fund is at more than $4,000.

Democrats have received a little dough, too. Senate Democratic Floor Leader Jim Ananich has collected nearly $2,000.

Overall, Republicans have raised more than $55,000.

Robinson: “That’s real money, that’s real money.”

Kesto has also collected some criticism. George Brikho owns a hydroponics store and claims Kesto’s real goal is to create a lucrative carve out within the marijuana industry that will benefit the Boji family. Kesto disagrees.

“As we set up a framework, people get a little jittery,” Kesto said. “They get scared about the future, and the model changing. And I don’t know what his issue is. But it sounds like it’s more than just the business. He may need some medicine.”

The Bojis cast a shadow over Lansing, and not just from the landmark tower they own across from the Capitol.

Ron Boji recently held a high-end fundraiser for Senate Majority Leader Mike Kowal at his palatial home. Even Gov. Rick Snyder passed through.

Kesto’s political accounts don’t show any recent contributions from Boji. but FOX 2 spied him huddling with Terrance Mansour of the Michigan Cannabis Development Association and a couple other fellows with strong opinions about medical marijuana reform.

Elrick: “Nobody has a leg up with you?” Kesto: “With me? No. I look out for the people of the state of Michigan.”

Sen. Jones also says the only influence he will come under, is what’s best for the good people of the great state of Michigan.

“You will never find, not once, somebody who bought me or bought a vote,” Jones said. “I’m the only guy in town that said ‘no’ to Matty Moroun.”

But there’s no denying that medical marijuana reform has been very good for Jones’ political action committee.

“Jones’ leadership PAC has really been moribund for years,” Robinson said. “And it certainly came to life in the last few months.”

The $14,000 that Jones’ PAC raised in the most recent filing period, is by far the most it has collected in a single reporting period since Jones founded it more than nine years ago.

Much, if not all, of that money came from folks with an interest in the medical marijuana reform legislation that just happens to be resting in the hands of Jones’ Senate Judiciary Committee.

Elrick: “How nice do you think it would be for the people of Michigan to say, ‘Here’s a guy who’s not going to take money because he thinks it’s might create at least the appearance of a conflict of interest?'”

“Well, I would have them look at any other legislator in town and they raise a lot more money than I do,” Jones said. “Some of them a great deal of money. And I don’t.”

Jones’ new-found fundraising prowess comes at a curious time. He is serving his last term in the Senate. Term limits mean his State House career ends in 2018.

Elrick: “Why continue to raise money? If there’s one guy in Michigan who could say: ‘I’m not even going to let people think I’m being influenced by you, it’s me, because I’m done.'”

“Every senator, every representative raises for their caucus,” Jones said. “Typically we’re asked to contribute $7,000 a year to the caucus, Republican or Democrat, either one, to assist with the re-election of other people. so that’s one reason to raise.

“The other reason to raise is that I can take care of the charities, whether it be veterans or children’s groups or hospice or Special Olympics. I can take care of those groups in my community.”

While it took in $14,000 this fall, Jones’ political action committee only cut two checks – one for $200 to the Michigan State University College Republicans and one for $100 to the friends of Sean Bertolino.

Elrick: “So the money that you’re raising now isn’t for your next campaign?”

“Never say never, I haven’t decided,” Jones said. “And I could transfer that. Say I were to run for governor, could I transfer that for a governor’s campaign? Yes, I could.”

Elrick: “And some of the money that you might use for higher office you’re getting it from people who might be spending it, so they can get higher themselves.”

“No,” Jones said. “No.”

Campaign accounts open to public inspection are not the only places lawmakers are loading up on loot. Jones and Kesto are like many politicians in Lansing and have non-profit accounts that don’t have to report where they get their money – or how they spend it.

Jones said that his non-profit has collected $5,000 from marijuana reformers and Kesto says he has only collected a couple thousand.

When it comes to contributors, Jones says nobody has influenced his vote. He says he has invited these people to fundraisers and if they chose to come and make a contribution that was their decision.

If marijuana gets legalized by voters, the reform efforts: Two separate movements: The Michigan Cannabis Coalition and MI Legalize who want to legalize recreational use of marijuana. They are now collecting signatures and they have to collect hundreds of thousands of signatures. That would go on the ballot in November, 2016 .

Watch The Report

Apr 5, 2016 | Legalization, News

DOWNTOWN PUBLICATIONS – BIRMINGHAM

By Katie Deska News staff

03/31/2016 – Approaching the eighth anniversary of the Michigan Medical Marijuana Act (MMMA), overwhelmingly approved by Michigan voters, the current political battle over cannabis centers not so much on whether or not the state should legalize recreational marijuana, but rather, it poses the question of when legalization will take effect, and who will control and profit from the million dollar industry. Fighting to appear on Michigan’s November 2016 ballot are three initiatives, each outlining a distinctly different approach to legalized recreational marijuana. At press time, only MILegalize and Abrogate Prohibition Michigan, two of the three groups that come from opposing schools of thought, were reaching out for support from the public and actively circulating petitions. The capital of the U.S., and four states – Oregon, Alaska, Washington, and Colorado – have already legalized marijuana for recreational use. Additionally, multiple cities around the country have passed ordinances decriminalizing the substance, effectively diluting the penalty of possession from a misdemeanor or felony, to a civil infraction. Ann Arbor was the first city in Michigan to decriminalize it in 1972. More than 30 years later, following the 2008 passage of the MMMA, an additional 17 municipalities followed suit, each crafting their own ordinance that defines the amount of marijuana to be in the bracket of civil infraction. Seven cities within Oakland County did so, namely, Huntington Woods, Pleasant Ridge, Berkley, Ferndale, Keego Harbor, Hazel Park, and Oak Park. Other areas in Michigan with decriminalization ordinances on the books include Detroit, Lansing, East Lansing, Grand Rapids, and Flint.

Despite growing acceptance of studies illustrating the effects of marijuana as a medical treatment, and increasing social approval of recreational use, the federal government maintains its classification of marijuana as a Schedule I controlled substance, a category defined by the drug enforcement agency as “the most dangerous class of drugs with a high potential for abuse and potentially severe psychological and/or physical dependence.” Heroin, LSD, ecstasy and peyote are listed next to cannabis. Comparatively, the second most dangerous category, Schedule II, includes cocaine, methamphetamine, Adderall, Ritalin, and Vicodin. “I certainly think it (marijuana) ought to be rescheduled,” said former Attorney General Eric Holder in an interview with P.B.S., recorded last September and released in February. “You know, we treat marijuana in the same way that we treat heroin now, and that clearly is not appropriate. So at a minimum, I think congress needs to do that. Then, I think we need to look at what happens in Colorado and what happens in Washington,” referring to two states that have profited immensely from legalized marijuana.

“In June, recreational marijuana sales hit $50 million for the first time, then in July sales rose over $55 million. If you add in medical marijuana sales, the total comes to $96 million for July, also higher than June’s total of $85 million. The portion of these sales in July that is earmarked for school construction projects is $3 million,” wrote Debra Borchardt in Forbes Magazine last fall of Colorado sales. Colorado voters approved recreational marijuana in 2012, the same year as Washington. “According to the Colorado Department of Revenue,” Borchardt’s article read, “the state has received nearly $70 million in tax revenue from marijuana from July 1, 2014 through June 30, 2015, easily beating the nearly $42 million in taxes on alcohol.”

Read the rest here

http://www.downtownpublications.com/1editorialbody.lasso?-token.folder=comm/2016/03/31&-token.story=222983.112113&-nothing&-token.disearea=2

Apr 5, 2016 | Legalization, Medical Marijuana, News, Uncategorized

2016 45th Annual Ann Arbor Hash Bash

The nation’s longest-running marijuana legalization rally runs from noon to 2 p.m. on the University of Michigan Diag, followed by the Monroe Street Fair.

Watch the video

Below is the full lineup for the rally:

- Matthew Abel, Detroit attorney and executive director of Michigan NORML

- Laith Al-Saadi, Ann Arbor musician

- Virg Bernero, Lansing mayor

- Statement by U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer read by Mark Passerini

- Sabra Briere, Ann Arbor City Council member

- Adam Brook, former Hash Bash organizer

- State Rep. Mike Callton, R-Nashville

- Tommy Chong, comedian and activist

- Scott Cecil, Students for Sensible Drug Policy outreach coordinator

- Stacia Cosner, Students for Sensible Drug Policy deputy director

- Alyssa Erwin, brain cancer survivor and medical marijuana patient

- Dori Edwards, Women Grow

- William Federspiel, Saginaw County sheriff

- Charmie Gholson, Michigan Moms United

- Jeffrey Hank, Michigan Comprehensive Cannabis Law Reform Initiative Committee

- State Rep. Jeff Irwin, D-Ann Arbor

- Brian Kardell, Students for Sensible Drug Policy at U-M

- Michael Komorn, Southfield attorney

- Jamie Lowell, co-founder of the 3rd Coast Compassion Center in Ypsilanti

- Reid Murdoch, Law Students for Sensible Drug Policy at U-M

- Mark Passerini, Ann Arbor Medical Cannabis Guild

- Dave Peters, Wayne State School of Medicine doctor

- Jim and Erin Powers, parents of pediatric medical cannabis patient Ryan Powers

- Chuck Ream, Safer Michigan director

- Robin Schneider, National Patients Rights Association legislative liaison

- Steve Sharpe, MI HEMP

- Dakota Serna, advocate for veterans equality

- DJ Short, known as the Willy Wonka of cannabis

- John Sinclair, poet and activist

- Marvin Surowitz- former professor and founder of the Partie Party

- John Ter Beek of Ter Beek vs. City of Wyoming

- Rick Thompson, The Compassion Chronicles

Apr 5, 2016 | Legalization, Medical Marijuana, News

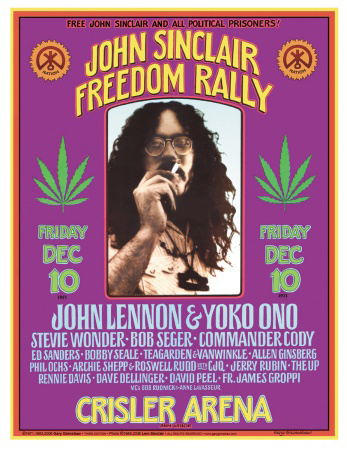

What started as a benefit concert for John Sinclair evolved into one of the most enduring marijuana protests in America.

Freedom Leaf Magazine / By Adam L. Brook

Any history of the Ann Arbor Hash Bash has to start with John Sinclair’s 10-year prison sentence in 1969 under Michigan’s felony marijuana laws, a punishment so outrageous that Abbie Hoffman interrupted the Who’s set at Woodstock to express his disapproval.

The December 10, 1971 “John Sinclair Freedom Rally” at Crisler Arena brought John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Stevie Wonder, Phil Ochs, Bob Seger, Archie Shepp, Allen Ginsberg, Bobby Seale ,and original Yippies Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, among others, to join Sinclair’s wife Leni, and advocate for his release. Lennon even wrote a new song for the occasion, “John Sinclair.”

Three days after the concert/rally, the Michigan Supreme Court ordered Sinclair released on an appeal bond from prison after serving almost two and a half years, while it considered the constitutionality of the law. The Court completed its review when it overturned Sinclair’s conviction on March 9, 1972, declaring that the statute violated the state Constitution’s equal protection clause for erroneously classifying marijuana as a narcotic.

On the heels of this decision, the Michigan legislature reclassified pot possession as a misdemeanor. But the new law didn’t take effect until April 3, 1972, creating a brief window of time where there was no state marijuana law on the books. To celebrate, anonymous founders jokingly suggested Ann Arbor’s first “Hash Festival” on April 1, 1972, putting up flyers promoting Pharaoh Sanders, Van Morrison and their own fictitious band. None of the three were actually going to appear, but the Michigan Daily picked up the story and people showed up on the Diag. According to the Daily, there were 500; police estimated 150 and made no arrests at what the Ann Arbor News called an “orderly festival.”

A few months later, Ann Arbor’s City Council passed an ordinance making marijuana possession a mere $5 civil fine, putting the city on the map as a beacon for proponents of cannabis reform.

The following year, Hash Bash boasted 5,000 participants, and featured unabashedly liberal and pro-marijuana legalization State Rep. Perry Bullard, who was photographed toking on a joint. Bullard went on to enjoy a successful 20-year career as Ann Arbor’s state representative.

Under a different mayor, the City Council repealed the new law after the ’73 Hash Bash, but a year later, a successful citywide referendum to entrench the $5 civil marijuana fine in the city charter was passed, making it impossible for the law to be overturned by a vote of the Council. More than 1,500 people showed up in 1974.

As early as 1977, the Michigan Daily lamented the event wasn’t the same as during the “good old days.” Two years later, the paper called for the end the of Hash Bash, which they termed a “disgusting farce” taken over by “belligerent and hostile” high school students.

Interest continued to wane, and the Michigan Daily and Ann Arbor News each eulogized the event as dead. After all, it was the Reagan “Say No to Drugs” era.

In 1986, the Daily reported, “At noon, about 130 people lit up, forming a ragged group that began at the brass M.”

But a change occurred in 1988, when 2,000 people showed up, thanks in a large part to a contingent of “Freedom Fighters” from High Times who entered the Diag dressed as colonial Minutemen, playing instruments and carrying a banner proclaiming “Pot Is Legal.”

In 1989, the Hash Bash crowd swelled to 5,000 again. That night, Michigan’s men’s basketball team edged Illinois to earn a trip to the national championship game (which it would win two days later).

The ensuring celebration on South University turned into a riot – which was cunningly blamed by UM President James Duderstadt not only on the Hash Bash, but on Deadheads arriving early for the April 5 and 6 Grateful Dead concerts. This prompted UM officials to publicly state they would deny the campus NORML chapter a permit to hold the Bash next year.

UM relented under strong pressure, but shockingly reversed course just weeks before the 1990 event, denying a permit. U of M NORML sued and won. Moreover, the University’s newly formed police force vowed to enforce state marijuana law, with its harsh criminal penalties. At the same time, the City Council placed a question on the ballot to increase the civil penalties for marijuana possession from $5 to $25, with increased sanctions for subsequent offenses.

In 1991, Hash Bash was moved from April 1 to the first Saturday in April. UM once again lost its court battle, and up to 10,000 people converged on the Diag.

During the ’90s, the event went from 2,000 to 10-12,000 attendees. Speakers like Tommy Chong, Chef Ra, Steve Hager, Jack Herer, Ed Rosenthal, Dana Beal, Ben Masel, Elvy Musikka, Gatewood Galbraith, Eric E. Sterling, The Lone Reefer, John Sinclair (who returned in ’96) and Stephen Gaskin were the main attractions.

Read the full article in Freedom Leaf Magazine digital edition here