Nov 28, 2017 | Blog, Michigan Medical Marijuana Criminal Defense Attorney Michael Komorn, News

Lansing— The road to the Michigan Capitol is lined with marijuana.

It’s almost impossible to drive to the capital dome without seeing scores of shop signs emblazoned with bright green medical crosses and plucky names — BudzRUs, TruReleaf, Best Buds, Kind Provisioning Center — all along Michigan Avenue and the city at large. A constant stream of people filter in and out of the pot shops.

In major cities such as Ann Arbor, Ypsilanti, Lansing and Flint, medical marijuana dispensaries are largely left alone.

In other areas, however, police follow federal and state law, in effect treating medical marijuana as an illegal narcotic and a public safety issue. Regional state police drug teams have raided and closed dispensaries with the help of county prosecutors across the state, including in Grand Traverse, Kent, Oscoda, Otsego, St. Clair and Wexford counties.

This unequal treatment occurs as Michigan implements new regulations on everything the industry does, from growing to transporting to selling. On Dec. 15, those trying to get into or stay in business can submit applications for an official state license.

It has been unclear since voters approved a 2008 referendum allowing marijuana for medical use what the state’s law actually permitted. In 2013, the Michigan Supreme Court decided that dispensaries are illegal.

But the ruling has left some communities without local access to medical pot while others have a glut. Still others face legal fees and prison.

“I’ve shed tears over this. This has never been about money for me,” said Chad Morrow, a 39-year-old Gaylord resident and former dispensary owner facing up to seven years in prison. “To have that taken away — it’s disheartening and heartbreaking, honestly.”

Although Morrow obtained permission from the Gaylord Planning Commission and the City Council to open a dispensary called Cloud 45, it was raided multiple times by a regional state police drug unit before he closed it in 2016 pending criminal charges.

Mixed messages from the state also helped inspire at least one medical marijuana crackdown in Grand Traverse County, the most recent county-wide enforcement action against dispensaries operating for years. Police sometimes conduct raids even if the prosecutor doesn’t play ball, said lawyers specializing in marijuana cases.

“I think Traverse City had the largest concentration of places north of Lansing, so it was the biggest target,” said Matt Abel, a criminal defense attorney in Detroit and an expert on marijuana cases. “Why they’re doing it now when these places have existed for years? It (makes us think) it has something to do with the upcoming licensing.

“They see this as an opportunity to clear the playing field and the patients be damned.”

Eight dispensaries closed

The prosecutor in Grand Traverse County helped close all eight of the county’s dispensaries in October after state regulators said staying open past the Dec. 15 application opening would hurt such shops’ chances of getting a license to do business legally.

In November, the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs changed course and issued an emergency rule telling pot shops that staying open past mid-December wouldn’t hurt their licensing chances. But Grand Traverse County prosecutor Robert Cooney already had issued cease-and-desist letters to the four medical marijuana shops in Traverse City and four others around the county.

Capt. Michael Caldwell, State Police commander for the region, said a regional state police drug unit called Traverse Narcotics Team, or TNT, acted “because dispensaries are illegal.”

Caldwell would not say why the probe began in September when the dispensaries were open for business for years beforehand.

“No, I can’t comment on any specifics of those investigations,” he said. “Once these owners obtain legal license to operate a dispensary, then they have nothing to fear. However, until that happens, they’re in violation of the Michigan Medical Marihuana Act, and they’re subject to enforcement action.”

Cooney said his cease-and-desist letters were in part prodded by comments from state Michigan Medical Marihuana Licensing Board member Donald Bailey, a retired state police sergeant from Traverse City who worked in drug enforcement. At an August meeting, Bailey said he wanted to close all dispensaries before licenses were issued to be in line with the Supreme Court ruling.

Bailey’s motion was met with sustained public outcry before LARA told the board at a later meeting that it does not have the authority to shut down dispensaries.

But Bailey’s comments and LARA’s prior warning that provisioning centers could sabotage their licensing chances by staying open past the mid-December application deadline led Cooney to believe the state wanted them shuttered.

“To me, (that) indicated that the state really wants these illegally operating business shut down before the new law,” he said, indicating he thought the state and localities wanted to collect taxes and licensing fees from legal businesses under new state rules.

Cooney informed the dispensaries in his letters that state law does not allow them to sell medical marijuana. The law allows a “caregiver” to cultivate and grow medical marijuana for up to five patients.

First Lt. Josh Lator, a state police commander at the Houghton Lake Post in northern Michigan, said police have been monitoring the Grand Traverse dispensaries for some time, and “the biggest reason” they acted now was “because every one of the places that the team contacted … were operating in violation of Michigan law.”

Licensed ‘caregivers’ lacking

Although dispensaries are currently illegal, many patients have argued that finding medical pot would be difficult if all the shops closed.

Michigan lacks enough licensed “caregivers” to provide for all of its patients. There are 272,215 patients and 43,266 caregivers in Michigan — or more than six patients for every caregiver. Caregivers can only grow medical marijuana for up to five patients each.

State police spokeswoman Shanon Banner said the department keeps no statistics on its medical marijuana dispensary raids, and that enforcement occurs on a “case-by-case” basis. She declined to say why some state police units crack down on dispensaries while others don’t.

“Sometimes enforcement is the result of local ordinance; sometimes it’s related to other criminal activity,” Banner said in an email.

But dispensaries across the state sell marijuana to more than five patients without legal repercussion.

“The county prosecutors let them do it,” said Barton Morris, a Royal Oak criminal defense attorney specializing in marijuana cases.

Pro-marijuana lawyers like Abel and Morris say the patchwork of enforcement happens in the absence of centralized state police orders. They say ambitious local narcotics units such as TNT work to find county prosecutors who are willing to cooperate.

By contrast, Washtenaw County prosecutor Brian Mackie said he deals with much more pressing issues. Local police and county prosecutors are just “inundated with domestic violence, murder, rape, armed robbery,” he said.

“Marijuana is not a No. 1 priority in the county,” said Mackie, who indicated he does not favor legalizing recreational use of marijuana. “We evaluate cases that come to us. We don’t get a great many of them.”

Registered business targeted

In 2016, 12 dispensaries in Oscoda and Otsego counties were raided by regional state police narcotics task forces.

In August of that year, the owners and workers of a dispensary called Northern Michigan Caregivers in Lewiston turned themselves into police following warrants issued for their arrest on charges that stemmed from running the dispensary.

Delbert Curio, 59, ran the shop with his wife, Brandi, for nearly four years before a judge issued a search warrant following two “controlled buys” to prove the dispensary actually sells medical marijuana.

Curio even took pains to register his business with the Oscoda County Clerk, according to a state police incident report.

“Delbert and Brandi (Curio) operated the business very openly and obviously with the belief that their transactions and activities would be protected by the Michigan Medical Marijuana (sic) Act,” defense lawyer Morris wrote in a 2016 sentencing memo.

The Straits Area Narcotics Unit still seized about $2,700 in cash and all of the shop’s marijuana and marijuana derivatives, such as liquid THC and edibles. The county prosecutor initially threatened Curio with up to 50 years in prison for delivering and manufacturing marijuana, operating or maintaining a laboratory and maintaining a drug house, according to a court document.

Instead, Delbert ended up getting four years of probation and permission from a local judge to use medical marijuana to treat his advanced lung cancer.

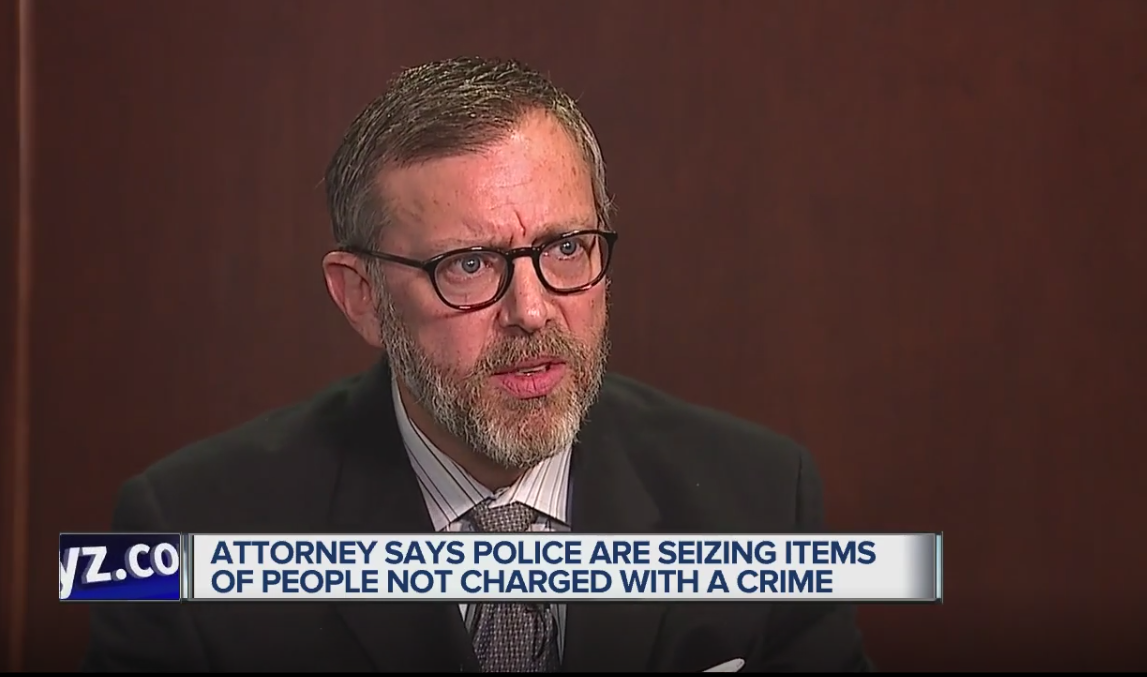

It’s incomprehensible that state police are still busting people as other state officials attempt to work out the regulatory details that will lay the groundwork for huge profits in the marijuana industry, said Michael Komorn, a Farmington Hills-based criminal defense lawyer specializing in marijuana cases.

“It can’t be reconciled with any kind of logic,” Komorn said.

mgerstein@detroitnews.com

Article Link

Nov 4, 2016 | Blog, Komorn Law Blog, Medical Marijuana, Michigan Medical Marijuana Criminal Defense Attorney Michael Komorn, News, Recent Victories, Victories Project

DETROIT, Mich. — A judge on Wednesday heard arguments in a federal class action lawsuit filed by medical marijuana patients and caregivers against several Michigan law enforcement and crime lab officials.

The suit, filed in June, claims that because of false lab reports, prosecutors are charging people with felonies without proof, illegally arresting them and seizing assets. Four patients and caregivers are suing the directors of the Michigan State Police, their crime labs and the publicly-operated Oakland County lab and that county’s sheriff.

Chief Judge Denise Page Hood of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan in Detroit said she will issue an opinion and decide whether the labs’ marijuana reporting policies violate the Fourth Amendment and due process rights of the medical marijuana patients and caregivers.

Read the plaintiffs’ lawsuit here.

Read the state defendants’ motion to dismiss here.

One of the four plaintiffs, Max Lorincz from Spring Lake, testified to having hash oil, but was charged with a felony for having synthetic THC. He lost custody of his 6-year-old son to foster care for 18 months until his case was dismissed; a case and statewide scandal FOX 17 broke last year.

“The problem is, the way that the Oakland County lab and the Michigan State Forensic Science Division is reporting still would allow for arrests, still would allow for these patients and caregivers to not have immunity because they’re reporting it as something other than marijuana,” said Michael Komorn, the plaintiffs’ attorney. “And the law enforcement community, as far as we know, is still arresting people for possessing these substances.”

In court Wednesday, Defense Attorney Rock Wood with the Michigan Attorney General’s office representing the state police and crime labs’ directors, along with Defense Attorney Nicole Tabin representing the Oakland County lab’s director and sheriff, declined requests for comment. Wood argued this is not a case involving altered, hidden or destroyed evidence. Instead, the defense writes in their motion to dismiss the case:

“The MSP policy is consistent with the current national standard for testing of seized drugs and avoids speculation as to the source of chemical components unless there is zero qualitative uncertainty.”

Ultimately, the labs’ policy states that unless there is marijuana plant matter seen along with THC, scientists label it “Schedule 1 THC, origin unknown,” instead of marijuana. This is the difference between a felony, or a marijuana possession misdemeanor which patients and caregivers can be immune for under the Michigan Medical Marijuana Act.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys and their experts say that 100 percent certainty for any evidence, even DNA is not possible.

“You know that nobody’s going to go through the trouble of synthesizing THC, along with other cannabinoids,” said Timothy Daniels, another attorney representing the plaintiffs. “And therefore you know to almost a 100 percent, and I won’t say 100 percent, let’s say 99 percent certainty, that is marijuana, not synthetic.”

Overall, the Michigan Medical Marijuana Act protects licensed patients and caregivers from charges and prosecution for having limited amounts of usable marijuana, not THC with an unknown origin. It’s this lab policy the suit is working to stop.

“It’s a little troubling that the defense is still suggesting their reporting practices are honorable,” said Komorn.

Statewide, as crime labs continue to report THC and marijuana in ways that many call controversial, the decision now rests in the judge’s hands. It’s a decision that could potentially reopen hundreds of cases across Michigan.

Meanwhile, recently passed legislation now legalizes medical marijuana patients and caregivers use of marijuana extracts like oils and edibles. The defense argued the lawsuit is moot in part due to this, however the plaintiffs’ attorneys stand firm that people continue to be unlawfully arrested, charged, and prosecuted for possession of extracts due to the labs’ reporting policy.

Jul 29, 2016 | Blog, Michigan Medical Marijuana Criminal Defense Attorney Michael Komorn, News

More than 800,000 people are arrested on marijuana charges each year in the United States, many on the basis of an error-prone test.

Raised in Montana and a resident of Alaska for 18 years, Robin Rae Brown, 48, always made time to explore in the wilderness. On March 20, 2009, she parked her pickup truck outside Weston, Florida, and hiked off the beaten path along a remote canal and into the woods to bird watch and commune with nature. “I saw a bobcat and an osprey,” she recalls. “I stopped once in a nice spot beneath a tree, sat down and gave prayers of thanksgiving to God.” For that purpose, Robin had packed a clay bowl and a “smudge stick,” a stalk-like bundle of sage, sweet grass, and lavender that she had bought at an airport gift shop in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Under the tree, she lit the end of the smudge stick and nestled it inside the bowl. She waved the smoke up toward her heart and over her head and prayed. Spiritual people from many cultures, including Native Americans, consider smoke to be sacred, she told me, and believe that it can carry their prayers to the heavens.

As darkness approached, she returned to her pickup truck to find Broward County’s Deputy Sheriff Dominic Raimondi and Florida Fish and Wildlife’s Lieutenant David Bingham looking inside the cab. The two men asked what she was doing and when she said she had been bird watching, Bingham asked whether she had binoculars. As she opened her knapsack, Officer Raimondi spotted her incense and asked if he could see it. He took the bowl and incense, asking whether it was marijuana. “No,” she recalls saying. “It’s my smudge, which is a blend of sage, sweet grass, and lavender.” “Smells like marijuana to me,” said Raimondi, who admitted he had never heard of a smudge stick. He then ordered Robin to stand by her truck, while he took the incense back to his car and conducted a common field test, known as a Duquenois-Levine, or D-L, test.

The result was positive for marijuana. Robin protested, telling them the smudge was available for purchase online for about $7 and gave them the name of a Web site that sold it — information Officer Bingham used his laptop to verify. But the men still searched her truck. After an hour and a half they finally allowed Robin to go home and told her that if a lab test confirmed the field test results, a warrant would be issued for her arrest. Exactly 90 days later, Robin was arrested at the spa in Weston, Florida where she has worked as a massage therapist for three years. She was handcuffed in front of clients and co-workers, and charged with felony possession of marijuana.

She was brought to a local police precinct in the town of Davie where she was booked and held for three hours. Unable to post the $1,000 bail because she was not allowed to call her boyfriend Michael, she was transferred to the Women’s Correctional Facility in Pompano Beach. At no time was she read her rights. Five hours after her arrest, she was finally allowed a brief phone call and left a message for Michael to post her bail. At the jail, a female officer came in and told Robin to take off all her clothes. She had already been searched at the precinct station and had her shoes, socks and bra confiscated. “I’m on my period,” she said. “I don’t care,” said the officer, who ordered her to pull her underwear down to her ankles, squat over the floor drain and cough.

The following morning at 4:30 a.m. she was released onto the streets of Pompano Beach with no idea where she was. The next day, Robin found a lab and submitted to voluntary hair and urine tests. These came back clean. She had previously worked for 16 years as a transportation systems specialist with the Federal Aviation Administration, a job that required airport security clearances, so drug tests were nothing new to her. During those years, she was frequently required to pass random drug and alcohol tests.

She later learned that her incense had never been subjected to a confirmatory lab test. She had been arrested and jailed solely on the basis of her positive D-L test results.

The Preferred Test for Marijuana

The Duquenois test was developed in the late 1930s by a French pharmacist, Pierre Duquénois, while he was working for the United Nations division of narcotics. In 1950, he completed a study for the UN which claimed that his test was “very specific” for marijuana; it was adopted by the UN and crime labs around the world as the preferred test for marijuana.

After undergoing several modifications, including the use of chloroform, the test became known as the Duquenois-Levine test, and became widely popular. Though scientists would show in the 1960s and 1970s that the D-L test was nonspecific, meaning it rendered false positives, it remains today the most commonly used test for marijuana — used in many of the 800,000 marijuana arrests that take place each year.

The test is a simple chemical color reagent test, easy to perform but difficult to interpret. To administer the test, a police officer simply has to break a seal on a tiny micropipette of chemicals, and insert a particle of the suspected substance; if the chemicals turn purple, this indicates the possibility of marijuana. But the color variations can be subtle, and readings can vary by examiner. The field test kits are produced by a variety of manufacturers, the most popular brands being NIK and ODV.

Literature about the D-L from NIK’s makers states that it is only a “screening” test that “may or may not yield a valid result” and may produce “false positive results.” Yet, since at least 1990, arresting officers, with the support of prosecutors, have regularly bypassed lab analysts and have purported to identify marijuana at hearings and trials only on the basis of visual inspection and the nonspecific D-L field test.

And the manufacturers have taken note.

In 1998, ODV reported in its newsletter with seeming satisfaction that a growing number of police departments were using its D-L field test, marketed as the NarcoPouch, as “their sole method of testing and identifying Marihuana [sic]…

To have Officers properly trained in identifying Marijuana and taking the Crime Lab out of the loop is a tremendous cost saving venture for the State…and gives the individual Officers testing the material a greater sense of satisfaction in completing their own cases” (emphasis added).

NIK, too, argued that depending exclusively on D-L field tests saves time and money. “Crime laboratories are so busy that drug tests take too long,” NIK states on its website. “With the cooperation of the Prosecuting Attorney, many police agencies have turned to presumptive drug testing. If the results indicate that an illegal substance is present, criminal charges may be filed.

In June 2006, the Virginia legislature went so far as to pass “emergency regulations” permitting law-enforcement officers to testify at trial for simple possession of marijuana cases solely on the basis of a D-L field test. Prior to these regulations, officers had to send suspected material to an approved lab for testing. Nothing in the new legislation specified that the field tests used had to be specific, or even accurate.

Frederic Whitehurst, a North Carolina-based defense attorney and former FBI special agent with a doctorate in chemistry, considers the law to be an unconstitutional usurpation of the authority of the courts to determine what test results can be admitted as valid evidence.

The trend toward police officers using the D-L as a confirmatory test has been encouraged by the National Institute of Justice, an agency of the Department of Justice which has funded programs to transform police officers into court experts, based on their use of these faulty field tests.

One such ongoing program for the Utah police claims to offer, in four days, “the necessary training” to positively identify marijuana, which would allow officers to serve as “expert witnesses in the courtroom setting.”

The program briefly covers the “botany, chemistry and analysis of marijuana preparations,” after which police officers, including street detectives and crime scene lab personnel, “will assume responsibility for all of their agency’s marijuana submissions.”

By the end of 2005, such submissions became the exclusive provenance of the Utah officers who had attended the training, and suspected marijuana samples were no longer accepted at the state lab for processing. In 2009, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation trained more than 1,600 police officers in the use of the D-L test, resulting in a 98 percent reduction in the use of marijuana lab tests. This troubling program garnered the bureau a 2009 Vollmer Excellence in Forensic Science Award by the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

Test ‘Should Never Be Relied Upon’ Despite its widespread use, as early as the 1960s, the D-L test had been proven incapable of definitively identifying the presence of marijuana in a seized substance.

A 1968 article in the Chemistry and Pharmacy Bulletin of Japan reported that the D-L tests “lack in adequate specificity.”

In 1969, M. J. de Faubert Maunder, a chemist in the Ministry of Technology, a UK government agency, documented the unreliability of the D-L test in an article in the Bulletin on Narcotics, noting that test results depended heavily on the subjective judgment of the analyst — and thus could easily vary dramatically from lab to lab.

“[A] positive test is not recorded until this colour has been identified,” he wrote, “and because it is almost impossible to describe in absolute terms it is best recognised by experience.”

Moreover, he reported finding twenty-five plant substances that would produce a D-L test result barely distinguishable from that of Cannabis and cautioned that the D-L test “should never be relied upon as the only positive evidence.”

Several articles in the Journal of Forensic Sciences further disproved any claims that the test could specifically identify marijuana.

A 1969 study in the journal reported false positive results from “a variety of vegetable extracts.”

A 1972 study found that the D-L test would test positive for many commonly occurring plant substances known as resorcinols, which are found in over-the-counter medicines. For instance, Sucrets lozenges tested positive for marijuana. This study concluded that the D-L test is useful only as a “screen” test and was not sufficiently selective to be relied upon for “identification.”

Still another study, in 1974, showed that 12 of 40 plant oils and extracts studied gave positive D-L test results.

In 1975, Dr. Marc Kurzman at the University of Minnesota, in collaboration with fourteen other scientists, published a study in The Journal of Criminal Defense that concluded: “The microscopic and chemical screening tests presently used in marijuana analysis are not specific even in combination for ‘marijuana’ defined in any way.”

In the 35 years since that study was published, no one has ever refuted this finding. Indeed, recent research has confirmed Kurzman’s findings.

In 2008, Whitehurst, the chemist and former FBI agent, substantiated Kurzman’s findings in an article in the Texas Tech Law Review. That same year, Dr. Omar Bagasra, director of the South Carolina Center for Biotechnology, conducted experiments in his lab also demonstrating that the D-L test is nonspecific and renders false positives. Bagasra, too, has impeccable credentials — he’s a leading pathologist and a board-certified forensic examiner.

A number of high courts have been persuaded by this evidence, and have found that the D-L test does not prove the presence of marijuana in a seized substance.

In 1973, the Supreme Court of Wisconsin ruled that the D-L test “standing alone is not sufficient to meet the burden of proving the identity of the substance beyond a reasonable doubt.” The court specifically noted that the D-L field tests used in this marijuana possession case “are not exclusive or specific for marijuana.”

Similarly, in 1979, a trial judge in North Carolina blocked the marijuana conviction of Richard Tate, which was to be based on positive D-L test results. In this case, too, the trial judge found that the D-L test was “not specific for marijuana” and had “no scientific acceptance as a reliable and accurate means of identifying the controlled substance marijuana.” On that basis, the judge allowed the defendant to suppress the use of the test results as evidence.

This finding was upheld by the North Carolina Supreme Court, which found that D-L test “was not scientifically acceptable because it was not specific for marijuana” and thus “the test results were properly suppressed.”

Also in 1979, the U.S. Supreme Court in Jackson v. Virginia ruled that the results of nonspecific tests could not be the basis for prosecution or conviction. In other words, if the only evidence is a positive D-L test, then the case must be dismissed. As noted, even the test’s manufacturers do not claim that their product can definitively identify marijuana.

The literature accompanying NIK’s NarcoPouch 908 cautions, “The results of a single test may or may not yield a valid result… There is no existing chemical reagent system, adaptable to field use, that will completely eliminate the occurrence of an occasional invalid test results [sic].

A complete forensic laboratory would be required to qualitatively identify an unknown suspect substance.” Shoddy Science Shoddy science, though, has muddied the waters. Several studies claim, falsely, to have validated the specificity of the D-L test. For instance, a seemingly authoritative 2000 study funded by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) purported to have validated the capacity of the D-L test to specifically and definitively identify marijuana. The title of the article, published in Forensic Science International, “Validation of Twelve Chemical Spot Tests for the Detection of Drugs of Abuse,” misstated the researchers’ actual findings. In fact, the study’s authors found that the twelve tests it analyzed, including the D-L, were nonspecific.

“The tests,” they wrote, “are not always specific for a single drug or class.” Speaking of the D-L test, they wrote that “mace, nutmeg and tea reacted with the modified Duquenois-Levine,” meaning that they produced false positives. They also noted, echoing Maunder’s 1969 article, that the D-L test is subjective: “The actual color…may vary depending on many factors [including] the color discrimination of the analyst.”

The best-known D-L “validation” study, and thus the most damaging to defendants, was published in 1972 by John Thornton and George Nakamura in Journal of Forensic Science Society. It instantly made the D-L test the gold standard across the country for marijuana identification.

But just like the NIST study, this report is internally contradictory and scientifically flawed. On the opening page of this article, the authors state that the D-L test is a “confirmation” test for marijuana.

Such a test must be capable of proving the presence of the drug beyond a reasonable doubt, specifically identifying the drug to the exclusion of all other possible substances and producing neither false positives nor false negatives.

However, the researchers’ own findings contradict their conclusion and show instead that the D-L test merely screens for marijuana. The authors themselves reported that the D-L test gave false positives and was not a confirmatory test even when cystolithic hairs — visible on the leaves of marijuana and other plants — are found on the suspected substance.

They claimed that “the Duquenois-Levine test is found to be useful in the confirmation of marijuana” when cystolithic hairs are observed “since none of the 82 species possessing hairs similar to those found on marijuana yield a positive test.” The problem is, as the authors noted, there are hundreds of plants with cystolithic hairs that they did not test, making their sample of eighty-two species woefully inadequate.

In effect, they admitted that the botanical exam itself was nonspecific. Combining two nonspecific tests does not make a specific, confirmatory test, as the D-L and the botanical exam both could easily render false positives.

Without having proved specificity, the authors nevertheless claimed it: “The specificity of the Duquenois reaction has been established, empirically at least, over the past three decades. No plant material other than marijuana has been found to give an identical reaction.”

They also noted its widespread use as if it were proof of its efficacy, mentioning that the D-L test was adopted as a preferential test by the League of Nations Sub-Committee of Cannabis and that a version of the test was proposed by the United Nations Committee on Narcotics as a specific test for marijuana.

(The UN subsequently found that only gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis could affirmatively identify marijuana.)

Inexplicably, this Thornton-Nakamura study is cited by the Drug Enforcement Administration and labs around the country as justifying the use of the D-L test alone or in combination with the microscopic visual exam for proving the presence of marijuana in a seized substance.

Even some courts have erroneously ruled that the D-L test is specific and confirmatory.

The most egregious example occurred in 2006. U.S. District Judge William Alsup found the D-L test to be a specific identification test and declared, grandiosely: “Despite the many hundreds of thousands of drug convictions in the criminal justice system in America, there has not been a single documented false-positive identification of marijuana or cocaine when the methods used by the SFPD [San Francisco Police Department] Crime Lab are applied by trained, competent analysts.” In fact, according to an affidavit in that case from a senior criminologist at the SFPD, its lab had, for forty years, used the D-L test in combination with a botanical exam to identify marijuana — two nonspecific tests that can each produce false positives. (A spokeswoman says that current SFPD policy is to subsequently confirm these results with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry.)

In March 2009, a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, speaking of the D-L and other tests, called the analysis of controlled substances “a mature forensic science discipline”; “one of the areas with a strong scientific underpinning”; and an area in which “there exists an adequate understanding of the uncertainties and potential errors.”

These incorrect assertions relied on assurances from government witnesses that “experienced forensic chemists and good forensic laboratories understand which tests (or combinations of tests) provide adequate reliability.”

The committee’s main witness was Joseph Bono, the former director of a regional DEA lab, who had previously issued a sworn affidavit, referring to the D-L and other forensic tests, which asserted that “tests and instruments that are properly used by qualified forensic chemists are incapable of producing a false positive.” But experience and competence cannot make a test specific if it is not — nor can they make it immune from false positives.

In 2008, Senator Jim Webb, D-VA, said, in announcing a proposed bill, that “the criminal justice system as we understand it today is broken, unfair.” This unfairness is visible every day in the disparate and contradictory court decisions regarding the admissibility of D-L test results.

Not only have courts contradicted one another on admissibility, but some courts have even chosen to admit the results of a D-L test while ruling that it does not prove the presence of marijuana beyond a reasonable doubt.

This patchwork of admissibility means that a person in one state can be convicted of possessing marijuana on the sole basis of the D-L test while a resident of another state cannot.

In 1978, the Supreme Court of Illinois in The People of the State of Illinois v. Peppe Park illustrated this confused, unconstitutional state of affairs.

In denying the admission of ipse dixit (“It’s marijuana because I say it’s marijuana”) reports, the court found that “police officers may not be presumed to possess the requisite expertise to identify a narcotic substance…because it simply is far too likely that a nonexpert would err in his conclusion on this matter, and taint the entire fact-finding process.”

This court cited a study that found 241 incorrect identifications of marijuana by arresting police officers. Yet in the same decision, the court erroneously claimed that “to determine accurately that a particular substance contains cannabis, all that is necessary is microscopic examination combined with the Duquenois-Levine test.”

Challenging the Test

Robin Rae Brown never even faced trial on marijuana possession charges. After she was released from jail, she retained this author as a defense expert.

When I first spoke with her attorney, Bill Ullman, he had never heard of the D-L test and said he normally plea-bargained cases like Robin’s. I urged him to challenge the test and provided him with several scientific studies cited in this article, relevant court decisions, including Jackson v. Virginia, and other information.

When Ullman made inquiries, he discovered that the sheriff’s department had never performed a lab test to confirm his field test results.

Robin, he discovered, had been charged with a felony solely on the basis of the D-L test and Officer Raimondi’s “opinion.”

At Ullman’s insistence, the sheriff’s department finally performed a gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis on Robin’s smudge, which came out negative.

State Attorney Berki Alvarez immediately dropped the charges against her, noting to Ullman, “the scariness that a person could be arrested under such conditions.”

Even scarier was the lab’s revelation that it does not conduct GC/MS analysis until just before a trial, as most marijuana possession defendants plea bargain before the trial.

If Robin had accepted a plea bargain, she would have been wrongfully convicted and saddled with a criminal record that could have damaged her future job prospects.

How many others before and since have accepted plea bargains based on false positives from a D-L test? “I am just now willing to share this story,” Robin wrote months after her arrest, “because it was embarrassing and I didn’t want to worry my family and friends.”

After some serious thought, she recently decided to file a lawsuit for wrongful arrest. “I would like to see them stop using the bogus field tests and to improve their procedures at the county crime lab,” she says. “I would like the public to be aware of the faulty field tests.” In truth, everyone arrested on marijuana charges has a Constitutional right to a GC/MS analysis.

Otherwise, they are being denied both due process and a fair trial. “It is not only unnecessary for the courts to continue to accept conclusory drug identifications based on nonspecific tests, it is also unwise for them to do so,” wrote Edward Imwinkelried, a professor of law at the University of California at Davis whose work on scientific evidence has been cited by the Supreme Court.

“Conclusory drug identification testimony is antithetical and offensive to the scientific tradition, and courts should not allow ipse dixit to masquerade as scientific testimony… Even more importantly, sustaining such drug identifications places a judicial imprimatur on testimony that cannot justifiably be labeled scientific. The rejection of such identifications is necessitated not only by due process but also by the simple demands of intellectual honesty.” Sustaining evidence from nonspecific tests like the D-L, he concludes, “is both bad science and bad law.”

This article was reported in collaboration with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute.

By John Kelly / AlterNet

July 27, 2010

John Kelly is a court-certified expert witness on drug tests and author of ‘False Positives Equal False Justice’ and the forthcoming book, ‘How to Obtain a Pretrial Dismissal of Marijuana Charges or an Acquittal.’ He can be contacted at: kjohn39679@aol.com.