Apr 5, 2016 | Legalization, Medical Marijuana, News

What started as a benefit concert for John Sinclair evolved into one of the most enduring marijuana protests in America.

Freedom Leaf Magazine / By Adam L. Brook

Any history of the Ann Arbor Hash Bash has to start with John Sinclair’s 10-year prison sentence in 1969 under Michigan’s felony marijuana laws, a punishment so outrageous that Abbie Hoffman interrupted the Who’s set at Woodstock to express his disapproval.

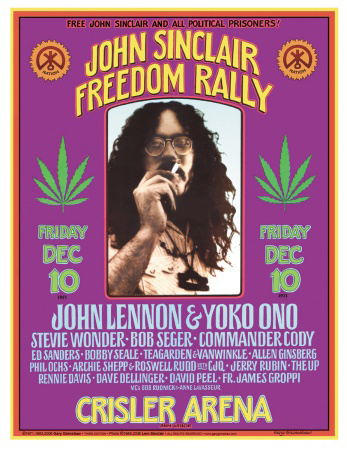

The December 10, 1971 “John Sinclair Freedom Rally” at Crisler Arena brought John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Stevie Wonder, Phil Ochs, Bob Seger, Archie Shepp, Allen Ginsberg, Bobby Seale ,and original Yippies Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, among others, to join Sinclair’s wife Leni, and advocate for his release. Lennon even wrote a new song for the occasion, “John Sinclair.”

Three days after the concert/rally, the Michigan Supreme Court ordered Sinclair released on an appeal bond from prison after serving almost two and a half years, while it considered the constitutionality of the law. The Court completed its review when it overturned Sinclair’s conviction on March 9, 1972, declaring that the statute violated the state Constitution’s equal protection clause for erroneously classifying marijuana as a narcotic.

On the heels of this decision, the Michigan legislature reclassified pot possession as a misdemeanor. But the new law didn’t take effect until April 3, 1972, creating a brief window of time where there was no state marijuana law on the books. To celebrate, anonymous founders jokingly suggested Ann Arbor’s first “Hash Festival” on April 1, 1972, putting up flyers promoting Pharaoh Sanders, Van Morrison and their own fictitious band. None of the three were actually going to appear, but the Michigan Daily picked up the story and people showed up on the Diag. According to the Daily, there were 500; police estimated 150 and made no arrests at what the Ann Arbor News called an “orderly festival.”

A few months later, Ann Arbor’s City Council passed an ordinance making marijuana possession a mere $5 civil fine, putting the city on the map as a beacon for proponents of cannabis reform.

The following year, Hash Bash boasted 5,000 participants, and featured unabashedly liberal and pro-marijuana legalization State Rep. Perry Bullard, who was photographed toking on a joint. Bullard went on to enjoy a successful 20-year career as Ann Arbor’s state representative.

Under a different mayor, the City Council repealed the new law after the ’73 Hash Bash, but a year later, a successful citywide referendum to entrench the $5 civil marijuana fine in the city charter was passed, making it impossible for the law to be overturned by a vote of the Council. More than 1,500 people showed up in 1974.

As early as 1977, the Michigan Daily lamented the event wasn’t the same as during the “good old days.” Two years later, the paper called for the end the of Hash Bash, which they termed a “disgusting farce” taken over by “belligerent and hostile” high school students.

Interest continued to wane, and the Michigan Daily and Ann Arbor News each eulogized the event as dead. After all, it was the Reagan “Say No to Drugs” era.

In 1986, the Daily reported, “At noon, about 130 people lit up, forming a ragged group that began at the brass M.”

But a change occurred in 1988, when 2,000 people showed up, thanks in a large part to a contingent of “Freedom Fighters” from High Times who entered the Diag dressed as colonial Minutemen, playing instruments and carrying a banner proclaiming “Pot Is Legal.”

In 1989, the Hash Bash crowd swelled to 5,000 again. That night, Michigan’s men’s basketball team edged Illinois to earn a trip to the national championship game (which it would win two days later).

The ensuring celebration on South University turned into a riot – which was cunningly blamed by UM President James Duderstadt not only on the Hash Bash, but on Deadheads arriving early for the April 5 and 6 Grateful Dead concerts. This prompted UM officials to publicly state they would deny the campus NORML chapter a permit to hold the Bash next year.

UM relented under strong pressure, but shockingly reversed course just weeks before the 1990 event, denying a permit. U of M NORML sued and won. Moreover, the University’s newly formed police force vowed to enforce state marijuana law, with its harsh criminal penalties. At the same time, the City Council placed a question on the ballot to increase the civil penalties for marijuana possession from $5 to $25, with increased sanctions for subsequent offenses.

In 1991, Hash Bash was moved from April 1 to the first Saturday in April. UM once again lost its court battle, and up to 10,000 people converged on the Diag.

During the ’90s, the event went from 2,000 to 10-12,000 attendees. Speakers like Tommy Chong, Chef Ra, Steve Hager, Jack Herer, Ed Rosenthal, Dana Beal, Ben Masel, Elvy Musikka, Gatewood Galbraith, Eric E. Sterling, The Lone Reefer, John Sinclair (who returned in ’96) and Stephen Gaskin were the main attractions.

Read the full article in Freedom Leaf Magazine digital edition here

Feb 19, 2016 | Blog, News

Michael Komorn was quoted in an article about Detroit law enforcement raiding dispensaries instead of licensing them.

“The current policy to shut down, raid and deny safe access is a losing hand to play,” said Michael Komorn, an attorney from Southfield and the 2015 ‘Right To Counsel Award’ winner. “Medical cannabis is a public health issue, not a public safety issue.”

“Detroit was one of remaining compassionate cities allowing safe access to medical cannabis. It has been difficult to watch the medical cannabis issue framed the way it has by the city government and community leaders. The lack of honest communication and dialogue seems to have detracted from diplomacy.”

Jan 14, 2016 | Blog, Criminal Defense Attorney Michael Komorn, Michigan Medical Marijuana Act, Michigan Medical Marijuana Association, Michigan Medical Marijuana Criminal Defense Attorney Michael Komorn, News

During this February 20, 2013 hearing, Assistant Oakland County Prosecutor Beth Hand notified the court that her office is contemplating filing criminal charges against a medical doctor for his involvement in certifying two medical marijuana patients, Robert Redden and Torey Clark.

The protracted case against Redden and Clark was initially dismissed back on June 17, 2009, but the district court’s dismissal was appealed by the Oakland County’s Prosecutor’s Office and, since then, the case has dragged on between various appellate and trial courts.

https://vimeo.com/60272365

Dec 31, 2015 | Blog, Michigan Medical Marijuana Act, News

Posted on BallotPedia

The Marijuana Legalization Initiative is an initiated state statute proposed for the Michigan ballot on November 8, 2016 ballot.

The measure would legalize, regulate and tax marijuana.

Adults age 21 and older would be permitted to possess and use marijuana and to cultivate 12 plants each. The initiative would also allow for hemp farming.

Text of measure

Ballot summary

An initiation of legislation to allow under state law the personal possession and use of marihuana by persons 21 years of age or older; to provide for the lawful cultivation and sale of marihuana and marihuana-infused products by persons 21 years of age or older; to permit the taxation of revenue derived from commercial marihuana facilities and to require that any such taxes be used for the purposes of education, public safety and public health; to permit the legislature to require licensing of commercial marihuana facilities by establishing a Michigan Cannabis Control Board, which board would be responsible for enforcement and administration of this act, including the promulgation of administrative rules.

The full text of the measure can be found here.

Support

The initiative campaign is being led by the Michigan Comprehensive Cannabis Law Reform Committee. The group is headed by Jeffrey Hank, who has organized local marijuana legalization initiative campaigns in Lansing and East Lansing, including one that appeared on the May 5, 2015, ballot.

Read the full post and see more stats and details

Dec 26, 2015 | Blog, Criminal Defense Attorney Michael Komorn, Medical Marijuana, Medical Marijuana Attorney Michael Komorn, News

Southfield — Three defense attorneys are asking the federal government to investigate the Michigan State Police crime laboratories, alleging misconduct in their testing for pending drug cases.

Southfield defense attorneys Neil Rockind and Michael Komorn, along with Michael Nichols of East Lansing, want the National Institute of Justice and the institute’s Office of Investigative and Forensic Sciences to look into their claims that the State Police lab has — on advice of the Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan — compromised results in marijuana cases.

According to Rockind, defense attorneys have obtained emails sent between lab officials and the association that allegedly show the labs were influenced by PAAM in its reporting of the testing of suspected marijuana in criminal cases and the origin of THC, the active component that produces the “high” obtained by the user.

“This involves how test results can show whether substances are synthetic, such as in designer drugs or from plant material,” Rockind said. “If synthetic, it can result in felony offenses punishable by up to seven years in prison rather than the more common misdemeanor offense or a crime in which medical marijuana card holders can advance a medical defense.”

State Police and the prosecutors association deny the attorneys’ allegations.

MSP crime labs received more than $236,000 this year in federal funding through the Paul Coverdell Forensic Science Improvement Grant Program. The grants are monitored by two federal agencies, Rockind said.

According to Rockind’s complaint, dated Tuesday, the emails reveal a “co-dependence between the Crime Lab and the prosecuting attorneys association that is the antithesis of an independent, objective and science focused forensic crime laboratory.”

“The problem is the interference by the prosecuting attorneys association with the reporting of scientific results,” Rockind wrote the agencies. “It reflects a culture that the Crime Lab and its analysts are not scientists reporting forensic analyses dispassionately in court through testimony. Instead, it reflects a systematic top-down management of the reporting by (PAAM) through the MSP laboratory supervisors.”

Rockind also wrote that the MSP crime labs have violated guidelines of the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Accreditation Board, which has accredited the lab.

Accredited labs nationally follow guidelines that include being impartial and objective, approaching all testing with an open mind and without bias, the complaint states.

Quoting the accrediting agency’s guidelines, Rockind wrote, labs must “conduct complete and unbiased examinations. Conclusions are based on the evidence and referenced material relevant to the evidence, not extraneous information, political pressure, or other outside influences.”

“The involvement and participation of the prosecuting attorney in the operation and conduct of the Crime Lab violates these guidelines,” Rockind wrote.

Rockind said he has not filed a lawsuit in the matter but only seeks to have supervisory officials review the situation, identify problems, if any, and determine corrective action.

Gerry LaPorte, a director of the two federal agencies both based in Washington, D.C., could not be reached for comment Wednesday.

Shanon Banner, a spokeswoman for the Michigan State Police, said, “The allegations of this group of defense attorneys are without merit.”

Banner said in 2013, the State Police Forensic Science Division changed its policy regarding how marijuana and THC are reported “in an effort to standardize reporting practices among our laboratories and to ensure laboratory reports only include findings that can be proved scientifically.”

Banner said that with an increase of synthetic drugs being sent to labs, “it became necessary to ensure reporting standards were in place across all labs.”

Lab workers were involved in discussions and proposed changes, she said, which included using the phrase “origin unknown” for samples where the source of the THC could not be scientifically proven to originate from plant-based material.

“It does not mean the sample is synthetic THC,” Banner stressed. “It only means the lab did not determine the origin, and the source of the THC should not be assumed from the lab results.”

“The allegation that politics or influence from any outside entity played a role in this policy change is wholly untrue,” Banner said. “Further, the MSP rejects the allegation that an internal policy change to ensure standardization regarding how test results are reported rises to the level of negligence or misconduct.”

PAAM president Mike Wendling issued a response Wednesday that said, in part, “defense attorneys have alleged that the PAAM directed the Michigan State Police Forensic Science Division to change their reporting procedures relating to THC in an effort to increase potential charges. These allegations are false.”

Wendling said the allegations are based on two emails in which Ken Stecker, a staff attorney, opined that “THC is a Schedule I drug, regardless of where it comes from.

“At no time, in either email, did Mr. Stecker direct MSP Forensic Science personnel on how to conduct tests or how to report their findings.

“When the MSP Forensic Science Division tests a substance that shows the presence of THC, the measurement of that THC is reported,” Wendling wrote. “If plant material is not detected to be present, they cannot determine if the THC is a synthetically created resin or created out of plant material.”

Wendling stressed that the crime labs set their own protocols for reporting scientific findings and described Stecker as a “highly regarded and highly requested statewide and national presenter on the issues of traffic safety and drug use.”

Mike Martindale

The Detroit News –5:50 p.m. EST December 23, 2015

mmartindale@detroitnews.com

Read Original Article