Oct 30, 2015 | Blog, Criminal Defense Attorney Michael Komorn, News

SPRING LAKE, Mich. – The defense representing a Spring Lake father facing a felony marijuana charge is accusing Michigan State Police Forensic Science Division crime labs of misreporting marijuana intentionally. It’s an allegation with statewide implications.

FOX 17 first reported Max Lorincz’s case in February: He’s a card-carrying medical marijuana patient. He was charged with felony possession of synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) for having a smear amount of butane hash oil (BHO).

“If nobody stands up for this and it just keeps going the way it is, how many more people are going to get thrown under the bus just for using their prescribed medicine?” asked Lorincz. “It’s just ridiculous.”

Lorincz said BHO, which is made from marijuana resins, is a prescription he uses for debilitating pain. On an unrelated medical emergency call for his wife, law enforcement found a smear of BHO in his family’s home. Now, in part as a result of the charges, Lorincz has lost custody of his six-year-old son, restricted to supervised public visits for the past several months.

After FOX 17 reported his case, attorney Michael Komorn at Komorn Law PLLC took Lorincz’s case pro bono.

Komorn said MSP crime labs, along with the Michigan attorney general’s office and the Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan, changed crime lab reporting policies for reporting marijuana back in 2013. Based on documents and emails received through the Freedom of Information Act, Komorn said state laboratories are falsely reporting marijuana as synthetic THC, essentially turning a misdemeanor charge into a felony.

“What is unique about this case is that they [the prosecution] are relying on the lab to report these substances so that they can escalate these crimes from misdemeanors to felonies,” said Komorn.

First charged with misdemeanor marijuana possession, Lorincz refused to plead guilty because he is a card-carrying medical marijuana patient. According to the Michigan Medical Marijuana Act, this charge can be dropped through Section 4 immunity, or Section 8 by asserting an affirmative defense.

However, the Ottawa County prosecutor charged Lorincz with felony synthetic THC possession, relying on the state lab report results from his BHO.

According to Lorincz’s crime lab report, technicians deemed his BHO to be “residue, delta-1-Tetrahydrocannabinol, schedule 1,” then the phrase, “origin unknown.”

The state lab scientist testified in an earlier April preliminary exam that they could not determine whether Lorincz’s BHO was natural or synthetic. However, the prosecution charged him with felony synthetic THC possession.

“When you have a laboratory that is looking at a substance and reporting it in a way that makes it a Schedule 1 instead of the marijuana they know it is, it’s creating a crime,” said Komorn.

“This is a lie,” Komorn said. “We have emails within the state laboratory communications indicating this, that they know it’s unlikely, more than unlikely near an impossible, that the patients and caregivers are in a laboratory synthesizing THC. It’s not happening, yet they report it as such.”

Komorn filed motions in Ottawa County Circuit Court in this case earlier this week. His firm is stating that the crime labs and prosecution are reporting “bogus crimes,” turning crime labs into a “crime factory.” He stands firm that the prosecution has no credible evidence to charge or convict Lorincz, especially since the state lab scientist testified they cannot prove the substance to be natural or synthetic.

“The lab as far as I’m concerned has lost its integrity,” said Komorn.

“You can’t play around with this type of thing and make stuff up and create crimes and be influenced by what the prosecutors want you to do and then come to court, take an oath, and expect to be received as an expert in forensic science. You’ve lost that.”

FOX 17 reached out to Michigan State Police for comment. The MSP public affairs department for the office of the director released this statement to FOX 17:

“The ultimate decision on what to charge an individual with rests with the prosecutor. The role of the laboratory is to determine whether marihuana or THC are present. Michigan state police laboratory policy was changed to include the statement “origin unknown” when it is not possible to determine if THC originates from a plant (marihuana) or synthetic means. This change makes it clear that the source of the THC should not be assumed from the lab results.”

FOX 17 has also reached out to the Michigan attorney general’s office and Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan for comment.

The motions filed in court are calling for an evidentiary hearing Nov. 5.

Posted 7:45 PM, October 28, 2015, by Dana Chicklas

Related Posts

a-non-stop-political-game-former-msp-forensic-science-director-on-false-marijuana-reporting

Michigan’s medical marijuana law circumvented by crime labs’ THC reports, attorney charges

Emails spell out alleged scandal in state crime lab testing, falsely reporting marijuana

Oct 26, 2015 | News

Last month, as the Michigan Senate debated a host of reforms to the state’s civil asset forfeiture laws, the Michigan State Police released its Asset Forfeiture Report, the annual publication required by state law that details Michigan’s drug-related forfeiture activities.

The report aggregates data from 629 local police departments, sheriff’s departments, and multijurisdictional task forces, plus the Michigan State Police. Civil forfeiture is a policy that enables law enforcement authorities to seize property or currency if they suspect it is involved in, or is the result of, a crime.

Americans Have Few Protections in Civil Proceedings. Forfeiture proceedings are civil, not criminal, property owners are afforded few due process protections!!

Since forfeiture proceedings are civil, not criminal, property owners are afforded few due process protections. With no presumption of innocence or right to an attorney, innocent property owners fighting the seizure of their homes and life savings face a legal landscape skewed against them in nearly every way possible.

According to Michigan’s forfeiture report, in 2014, state law enforcement agencies seized and forfeited $23.9 million’s worth of cash and property. That sum includes more than $14 million’s worth of assets forfeited under state law, and an additional $8 million provided to Michigan law enforcement agencies via the federal equitable sharing program.

The real total value of forfeited property is likely higher, since only drug-related forfeitures have to be reported.

Taking into account the cost of running forfeiture operations, Michigan law enforcement netted a cool $20.4 million in revenue, every penny of which they can spend without political oversight and with little accountability—conditions that are ripe for abuse.

Believe it or not, the 12 pages that constitute this year’s forfeiture report are the most detailed look Michiganders and their elected lawmakers get into the world of civil forfeiture.

Here are some of the highlights:

• 8,558 cases—80 percent of all forfeiture cases in Michigan—were so-called “administrative forfeitures,” meaning that they never saw the inside of a courtroom. Instead, a law enforcement agency—often the agency that made the initial seizure and stands to gain financially from the forfeiture, acts as judge, prosecutor, and jury all in one.

• The number-one forfeiture target in Michigan is cash. Michigan law enforcement agencies seized $11.1 million in cold hard cash last year, which accounts for 79 percent of the value of all seized assets and property that were forfeited under state law. Cash presents a particularly inviting target for law enforcement agents. Most bills in circulation are tainted with narcotics, making drug-dog “alerts”—a frequent justification for cash seizures—exceedingly likely, even if the owner has nothing whatsoever to do with the drug trade.

• “Conveyances”—vehicles and vessels allegedly used to transport drugs or drug proceeds—were the second-largest category of forfeited item. Michigan forfeited 2,212 vehicles and four vessels last year, for a total value to law enforcement of $1.9 million. Detroit police in particular have faced sharp criticism for their propensity to seize vehicles on highly dubious grounds. In 2008, 44 vehicles were seized from the patrons of the Detroit Contemporary Art Institute’s “Funk Night,” because the museum had failed to obtain a liquor license. Each patron had to pay $900 to get his car back, and a judge later ruled the seizures unconstitutional.

• Twelve percent of forfeiture funds were used to cover the cost of personnel and overtime, placing individual members of the law enforcement community directly and personally reliant on forfeiture for their livelihoods, a significant conflict of interest.

A Margarita Machine?

Forty-four point six percent of forfeiture revenues were used for equipment purchases. While much, if not most, of this category may be above-board (bulletproof gear or body cameras, for example), law enforcement agencies around the country have faced criticism for using forfeiture funds to buy all manner of “equipment” ranging from the outlandish (helicopters and armored personnel carriers) to the absurd (margarita machines).

Law enforcement agencies should be generously funded and fully equipped, but the opacity of forfeiture-related purchases makes it impossible to separate the good from the bad.

The report raises as many questions as it purports to answer.

How many property seizures were accompanied by criminal charges and convictions? How much additional forfeiture revenues were generated in cases unrelated to drugs? What equipment is law enforcement buying with its untraced millions? Why are personnel directly financed by forfeiture funds, given the obvious conflict of interest? And why did 56 agencies not file any documentation whatsoever?

Reform is Badly Needed

Fortunately, answers to these questions may be forthcoming. Last week, the Michigan state Senate unanimously passed a modest reform package that greatly enhances the reporting requirements for law enforcement.

If Gov. Rick Snyder, R-Mich., signs the seven-bill package, Michiganders will finally get to see exactly how often civil forfeiture is accompanied by criminal charges and convictions, and exactly how forfeiture funds are being spent.

The reform package also raises the evidentiary standard in forfeiture cases from a “preponderance of the evidence” to “clear and convincing,” a much more fitting standard, given that what is often at stake are people’s homes and life savings.

Read the Report

Original Post

Jason Snead / @jasonwsnead / October 16, 2015 /

Oct 10, 2015 | Blog, News

The National Security Agency’s spying tactics are being intensely scrutinized following the recent leaks of secret documents. However, the NSA isn’t the only US government agency using controversial surveillance methods.

Monitoring citizens’ cell phones without their knowledge is a booming business. From Arizona to California, Florida to Texas, state and federal authorities have been quietly investing millions of dollars acquiring clandestine mobile phone surveillance equipment in the past decade.

Earlier this year, a covert tool called the “Stingray” that can gather data from hundreds of phones over targeted areas attracted international attention. Rights groups alleged that its use could be unlawful. But the same company that exclusively manufacturers the Stingray—Florida-based Harris Corporation—has for years been selling government agencies an entire range of secretive mobile phone surveillance technologies from a catalogue that it conceals from the public on national security grounds.

Details about the devices are not disclosed on the Harris website, and marketing materials come with a warning that anyone distributing them outside law enforcement agencies or telecom firms could be committing a crime punishable by up to five years in jail.

These little-known cousins of the Stingray cannot only track movements—they can also perform denial-of-service attacks on phones and intercept conversations. Since 2004, Harris has earned more than $40 million from spy technology contracts with city, state, and federal authorities in the US, according to procurement records.

In an effort to inform the debate around controversial covert government tactics, Ars has compiled a list of this equipment by scrutinizing publicly available purchasing contracts published on government websites and marketing materials obtained through equipment resellers. Disclosed, in some cases for the first time, are photographs of the Harris spy tools, their cost, names, capabilities, and the agencies known to have purchased them.

What follows is the most comprehensive picture to date of the mobile phone surveillance technology that has been deployed in the US over the past decade.

“Stingray”

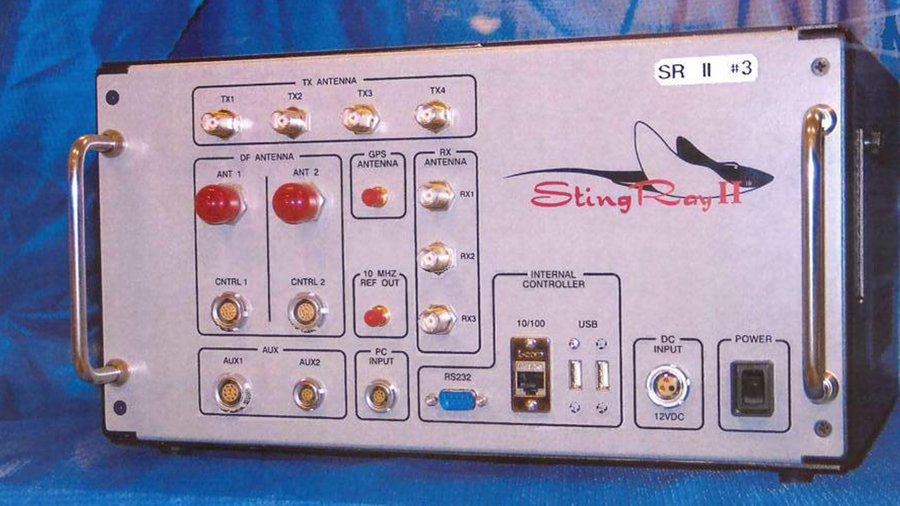

The Stingray has become the most widely known and contentious spy tool used by government agencies to track mobile phones, in part due to an Arizona court case that called the legality of its use into question. It’s a box-shaped portable device, sometimes described as an “IMSI catcher,” that gathers information from phones by sending out a signal that tricks them into connecting to it. The Stingray can be covertly set up virtually anywhere—in the back of a vehicle, for instance—and can be used over a targeted radius to collect hundreds of unique phone identifying codes, such as the International Mobile Subscriber Number (IMSI) and the Electronic Serial Number (ESM). The authorities can then hone in on specific phones of interest to monitor the location of the user in real time or use the spy tool to log a record of all phones in a targeted area at a particular time.

The FBI uses the Stingray to track suspects and says that it does not use the tool to intercept the content of communications.

However, this capability does exist. Procurement documents indicate that the Stingray can also be used with software called “FishHawk,” (PDF) which boosts the device’s capabilities by allowing authorities to eavesdrop on conversations. Other similar Harris software includes “Porpoise,” which is sold on a USB drive and is designed to be installed on a laptop and used in conjunction with transceivers—possibly including the Stingray—for surveillance of text messages.

Similar devices are sold by other government spy technology suppliers, but US authorities appear to use Harris equipment exclusively. They’ve awarded the company “sole source” contracts because its spy tools provide capabilities that authorities claim other companies do not offer. The Stingray has become so popular, in fact, that “Stingray” has become a generic name used informally to describe all kinds of IMSI catcher-style devices.

First used: Trademark records show that a registration for the Stingray was first filed in August 2001. Earlier versions of the technology—sometimes described as “digital analyzers” or “cell site simulators” by the FBI—were being deployed in the mid-1990s. An upgraded version of the Stingray, named the “Stingray II,” was introduced to the spy tech market by Harris Corp. between 2007 and 2008. Photographs filed with the US Patent and Trademark Office depict the Stingray II as a more sophisticated device, with many additional USB inputs and a switch for a “GPS antenna,” which is likely used to assist in location tracking.

Cost: $68,479 for the original Stingray; $134,952 for Stingray II.

Agencies: Federal authorities have spent more than $30 million on Stingrays and related equipment and training since 2004, according to procurement records. Purchasing agencies include the FBI, DEA, Secret Service, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Internal Revenue Service, the Army, and the Navy. Cops in Arizona, Maryland, Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and California have also either purchased or considered purchasing the devices, according to public records. In one case, procurement records (PDF) show cops in Miami obtained a Stingray to monitor phones at a free trade conference held in Miami in 2003.

“Gossamer”

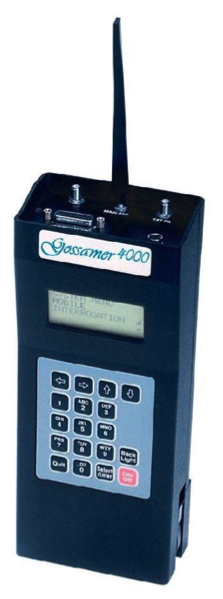

The Gossamer is a small portable device that can be used to secretly gather data on mobile phones operating in a target area. It sends out a covert signal that tricks phones into handing over their unique codes—such as the IMSI and TMSI—which can be used to identify users and home in on specific devices of interest. What makes it different from the Stingray? Not only is the Gossamer much smaller, but it can also be used to perform a denial-of-service attack on phone users, blocking targeted people from making or receiving calls, according to marketing materials (PDF) published by a Brazilian reseller of the Harris equipment. The Gossamer has the appearance of a clunky-looking handheld transceiver. One photograph filed with the US Patent and Trademark Office shows it displaying an option for “mobile interrogation” on its small LCD screen, which sits above a telephone-style keypad.

First used: Trademark records show that a registration for the Gossamer was first filed in October 2001.

Cost: $19,696.

Agencies: Between 2005 and 2009, the FBI, Special Operations Command, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement spent more than $1.3 million purchasing Harris’ Gossamer technology and upgrading existing Gossamer units, according to procurement records. Most of the $1.3 million was spent by the FBI as part of a large contract in 2005.

“Triggerfish”

The Triggerfish is an eavesdropping device. It allows authorities to covertly intercept mobile phone conversations in real time. This sets it apart from the original version of the Stingray, which marketing documents suggest was designed mainly for location monitoring and gathering metadata (though software can allow the Stingray to eavesdrop). The Triggerfish, which looks similar in size to the Stingray, can also be used to identify the location from which a phone call is being made. It can gather large amounts of data on users over a targeted area, allowing authorities to view identifying codes of up to 60,000 different phones at one time, according to marketing materials.

First used: Trademark records show that a registration for the Triggerfish was filed in July 2001, though its “first use anywhere” is listed as November 1997. It is not clear whether the Triggerfish is still for sale or whether its name has recently changed, as the trademark on the device was canceled in 2008, and it does not appear on Harris’ current federal price lists.

Cost: Between $90,000 and $102,000.

Agencies: The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; the DEA; and county cops in Miami-Dade invested in Triggerfish technology prior to 2004, according to procurement records. However, the procurement records (PDF) also show that the Miami-Dade authorities complained that the device “provided access” only to Cingular and AT&T wireless network carriers. (This was before the two companies merged.) To remedy that, the force complemented the Triggerfish tool with additional Harris technology, including the Stingray and Amberjack, which enabled monitoring of Metro PCS, Sprint, and Verizon. This gave the cops “the ability to track approximately ninety percent of the wireless industry,” the procurement documents state.

“Kingfish”

The Kingfish is a surveillance transceiver that allows authorities to track and mine information from mobile phones over a targeted area. The device does not appear to enable interception of communications; instead, it can covertly gather unique identity codes and show connections between phones and numbers being dialed. It is smaller than the Stingray, black and gray in color, and can be controlled wirelessly by a conventional notebook PC using Bluetooth. You can even conceal it in a discreet-looking briefcase, according to marketing brochures.

First used: Trademark records show that a registration for the Kingfish was filed in August 2001. Its “first use anywhere” is listed in records as December 2003.

Cost: $25,349.

Agencies: Government agencies have spent about $13 million on Kingfish technology since 2006, sometimes as part of what is described in procurement documents as a “vehicular package” deal that includes a Stingray. The US Marshals Service; Secret Service; Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; Army; Air Force; state cops in Florida; county cops in Maricopa, Arizona; and Special Operations Command have all purchased a Kingfish in recent years.

“Amberjack”

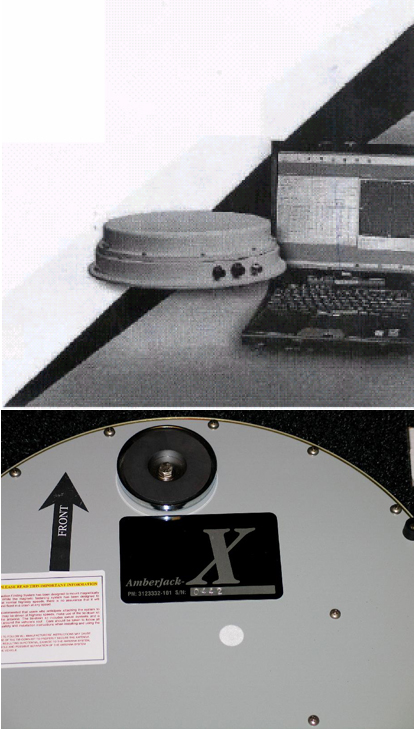

The Amberjack is an antenna that is used to help track and locate mobile phones. It is designed to be used in conjunction with the Stingray, Gossamer, and Kingfish as a “direction-finding system” (PDF) that monitors the signal strength of the targeted phone in order to home in on the suspect’s location in real time. The device comes inbuilt with magnets so it can be attached to the roof of a police vehicle, and it has been designed to have a “low profile” for covert purposes. A photograph of the Amberjack filed with a trademark application reveals that the device, which is metallic and circular in shape, comes with a “tie-down kit” to prevent it from falling off the roof of a vehicle that is being driven at “highway speeds.”

First used: Trademark records show that a registration for the Amberjack was filed in August 2001 at the same time as the Stingray. Its “first use anywhere” is listed in records as October 2002.

Cost: $35,015

Agencies: The DEA; FBI; Special Operations Command; Secret Service; the Navy; the US Marshals Service; and cops in North Carolina, Florida, and Texas have all purchased Amberjack technology, according to procurement records.

“Harpoon”

The Harpoon is an “amplifier” (PDF) that can boost the signal of a Stingray or Kingfish device, allowing it to project its surveillance signal farther or from a greater distance depending on the location of the targets. A photograph filed with the US Patent and Trademark Office shows that the device has two handles for carrying and a silver, metallic front with a series of inputs that allow it to be connected to other mobile phone spy devices.

First used: Trademark records show that a filing for the Harpoon was filed in June 2008.

Cost: $16,000 to $19,000.

Agencies: The DEA; state cops in Florida; city cops in Tempe, Arizona; the Army; and the Navy are among those to have purchased Harpoons since 2009.

“Hailstorm”

The Hailstorm is the latest in the line of mobile phone tracking tools that Harris Corp. is offering authorities. However, few details about it have trickled into the public domain. It can be purchased as a standalone unit or as an upgrade to the Stingray or Kingfish, which suggests that it has the same functionality as these devices but has been tweaked with new or more advanced capabilities. Procurement documents (PDF) show that Harris Corp. has, in at least one case, recommended that authorities use the Hailstorm in conjunction with software made by Nebraska-based surveillance company Pen-Link. The Pen-Link software appears to enable authorities deploying the Hailstorm to directly communicate with cell phone carriers over an Internet connection, possibly to help coordinate the surveillance of targeted individuals.

First used: Unknown.

Cost: $169,602 as a standalone unit. The price is reduced when purchased as an upgrade.

Agencies: Public records show that earlier this year, the Baltimore Police Department, county cops in Oakland County, Michigan, and city cops in Phoenix, Arizona, each separately entered the procurement process to obtain the Hailstorm equipment. The Baltimore and Phoenix forces each set aside about $100,000 for the device, and they purchased it as an upgrade to Stingray II mobile phone spy technology. The Phoenix cops spent an additional $10,000 on Hailstorm training sessions conducted by Harris Corp. in Melbourne, Florida, and Oakland County authorities said they obtained a grant from the Department of Homeland Security to help finance the procurement of the Hailstorm tool. The Oakland authorities noted that the device was needed for “pinpoint tracking of criminal activity.” It is highly likely that other authorities—particularly federal agencies—will invest in the Hailstorm too, with procurement records eventually surfacing later this year or into 2014.

No one’s talking

The FBI has previously stated in response to questions about the Stingray device that it “strives to protect our country and its people using every available tool” and that location data in particular is a “vital component” of investigations. But when it comes to discussing specific surveillance equipment, it is common for the authorities to remain tight-lipped because they don’t want to reveal tactics to criminals.

The code of silence shrouding the above tools, however, is highly contentious. Their use by law enforcement agencies is in a legal gray zone, particularly because interference with communications signals is supposed to be prohibited under the federal Communications Act. In May, an Arizona court ruled that the FBI’s use of a Stingray was lawful in a case involving conspiracy, wire fraud, and identity theft. But according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), when seeking authorization for the use of the Stingray tool, the feds have sometimes unlawfully withheld information from judges about the full scope of its capabilities. This means that judges across the country are potentially authorizing the use of the technology without even knowing what it actually does.

That’s not all. There is another significant issue raised by the Harris spy devices: security. According to Christopher Soghoian, chief technologist at the ACLU, similar covert surveillance technology is being manufactured by a host of companies in other countries like China and Russia. He believes the US government’s “state secrecy” on the subject is putting Americans at risk.

“Our government is sitting on a security flaw that impacts every phone in the country,” Soghoian says. “If we don’t talk about Stingray-style tools and the flaws that they exploit, we can’t defend ourselves against foreign governments and criminals using this equipment, too.”

Oct 10, 2015 | Blog, Komorn Law Blog, News

Cell Phone Surveillance

Cellular communications are inherently vulnerable as they pass through the air. Whereas it was once required to physically tap into a wire based network in order to deploy surveillance methods, cellular transmissions allow practically anyone with the desire to intercept our voice, text, and data transmissions completely anonymously.

The concept of eavesdropping on cellular communications is nothing new, in the time of analog cellphones a basic scanner was all that was needed. In 1993 before a congressional committee a man presented a modified scanner that allowed everyone in the room to listen to nearby cellular conversations. Congress banned the sale of such scanners, but since then there hasn’t been much serious public policy debate on the issue.

Technology has obviously come a long way since 1993, and the cellular networks in place today are highly vulnerable to surveillance from criminals and governments alike. Many federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies have equipment designed for military use with surveillance capabilities that far exceed the scanners from the days of analog. They’re indiscriminate by their very nature, sometimes collecting data on tens of thousands of phones at a time. They’re used anonymously with virtually no oversight, with no record that they’ve been used, and often without a warrant.

The recent policy change announced by the DOJ last week is welcomed and long overdue, but is the cat already out of the bag rendering this policy change too little too late? Some say we need to systemically address current vulnerabilities in our cellular networks as a whole, as well as initiate a more thorough update to legislation of cellular surveillance.

This is especially true here in Michigan where local law enforcement agencies have the most highly sophisticated surveillance equipment with capabilities that raise a variety of Fourth Amendment and other Constitutional concerns.

Legislative bills were filed in Michigan last year by a former State Rep that would have provided much needed oversight and regulations regarding these technologies, but unfortunately they didn’t get any traction. Everyone is very tight lipped. Why are law enforcement and our legislators so unwilling to discuss this topic?

Guise of Secrecy

One major reason why there’s an utter lack of public debate on this surveillance is rooted under the guise of its supposed secrecy. I say guise because they’re not really secrets at all, this surveillance has been outlined in full detail in the Harvard Journal of Law and Technology, as well as a number of other sources.

However, law enforcement often hide behind non-disclosure agreements, and the Homeland Security Act which they claim prevent them from speaking publicly about these technologies, even going so far as withholding information from the courts. The government considers their use of this surveillance to be “law enforcement sensitive information”, and they’ve gone to great lengths to protect the shroud of secrecy. It wasn’t until after a decade after their initial use that this technology, in this case called Stingray, was first revealed in a pretrial criminal case. Rather than disclose information about it the government dropped the charges. The majority of what is known about this surveillance has been acquired through highly redacted Freedom of Information Act requests.

One might ask themselves how it’s possible that such powerful surveillance tools wouldn’t have come up in a criminal case sooner, and the answer is the use of this technology is often concealed by law enforcement with misleading source descriptions, often referring to their source as a “confidential informant” when in fact the evidence was acquired through cellular surveillance.

In some cases law enforcement and prosecutors have been shown to have mislead judges not only about their use of these technologies, but also the capabilities of the technologies themselves citing the need to do so based on proprietary non-disclosure agreements.

Equally indicative of the lack of oversight is that in some situations evidence has even been withheld from criminal defendants. The manufacturers of these devices themselves have even been less than forthright when representing their products to the FCC to secure licensing.

Regardless of law enforcement’s attempts to keep them secret these devices like the Stingray and others, as well as the vulnerabilities they exploit are widely known. They’ve been widely reported on, depicted in movies, can be purchased by anyone, and at this point they’re even produced at home by hobbyists for relatively little money.

Herein lies part of the problem. A device that costs law enforcement agencies over $100k to purchase can now be purchased online by anyone for less than $2000. Governments no longer monopolize the cellular surveillance market. The vulnerabilities in our networks are no longer secrets, and the prevention of serious public discussion about these technologies under the guise of non-disclosure agreements and DHS laws are in fact leaving all of us vulnerable to bad actors that extend well beyond our government. There has even been commercial interests from stores seeking to track their customer’s movements.

Here in Michigan we know at the very least Oakland County law enforcement have the most advanced military grade surveillance equipment available called Hailstorm.

According to statements made last year to the Oakland Press by Sheriff Michael Bouchard similar devices are believed to be in use elsewhere in the state too. Sheriff Bouchard claimed that: “It’s not a surveillance device … It’s not capturing metadata or personal data of any kind. It does not record calls of any kind.” When asked for further comment on how this technology works the sheriff’s department and the representatives of the company that make Hailstorm both cited Homeland Security Act and proprietary laws that restrict them from talking about it.

Sound familiar?

So what exactly is this super-secret technology that according to Sheriff Bouchard isn’t a surveillance device? On the purchase form Undersheriff Michael McCabe lists the description as “allows for pinpoint tracking of criminal activity”. Is that really all it does, or do these statements simply fall in line with the systematic misrepresentation of the all-you-can-eat surveillance buffet currently hidden under the guise of secrecy by law enforcement?

Carrier-Assisted Surveillance

Generally when we think of cellular communication surveillance we think of carrier-assisted surveillance where the telecommunications companies themselves provide and/or enable surveillance for law enforcement. They’ve been providing such services for over 100 years and generally have teams of compliance officers that help facilitate and keep record of these services which provide a necessary check to balance out law enforcement’s use of such surveillance powers.

This type of carrier-assisted surveillance is generally limited to specific telephone or other identifying numbers and legally requires a Pen/Trap order or a warrant depending on the type of surveillance. Carrier-assisted surveillance is not what we’re discussing here.

IMSI Catchers (aka Stingray/Hailstorm)

Here we’re discussing the ability of independent federal, state, and local agencies, as well as criminals, to set up fake cell sites indiscriminately monitoring all cellphones within their vicinity, tricking them into providing data and even complete control.

These devices are called IMSI catchers, the most widely used by law enforcement are the Stingray and Hailstorm manufactured by Harris Corp, and these are the machines stealing your cellular data. Contrary to Sheriff Bouchard’s claim that these are not surveillance devices and do not capture data, this is precisely what they do.

IMSI catchers are radio devices that can be used to capture and decrypt transmissions between cellphones and cell towers, as well as simulate cell towers constantly pinging cellphones within their vicinity in order to trick the cellphones into connecting to it whether the phone is in use or not. IMSI catchers can be used to identify, locate, monitor, gain access, and in some cases gain complete control of cellphones within their vicinity.

Despite law enforcement’s best attempts to keep it secret the IMSI catcher that has gained the most notoriety due to their widespread use of it is the Stingray. Its use and legal implication in criminal trials have been detailed in a document published by the ACLU. Many federal, state, and local agencies own and operate Stingray’s across the country.

Not even congress can get law enforcement to tell them exactly how many agencies use them. By itself the Stingray enables anonymous and indiscriminate collection of metadata like location, and the real-time collection of incoming and outgoing numbers of all cellphones within its vicinity without leaving a record that it’s ever been used.

More worrisome, when used with additional programs, or an array of additional products provided by the manufacturer, its surveillance capabilities extend into enabling the real-time monitoring of data, text, and voice transmissions. All of which can be enabled anonymously by the operator without anyone knowing they’ve done so. It’s kind of like a “look but don’t touch” policy towards surveillance and it’s currently being enforced on the honor system with no oversight. As is the case with Oakland County Sheriffs department, the capabilities of these devices are often downplayed and outright misrepresented, even to judges.

Even more egregious and powerful is the IMSI catcher called the dirtbox. The dirtbox has been flown over metropolitan areas across the country from planes operated by US Marshals who collect data on up to tens of thousands of cellphones at a time.

All without a warrant.

The most cutting edge and powerful IMSI catcher available to law enforcement (that we’re aware of) is the military grade Hailstorm. Despite Sheriff Bouchard’s claims, Hailstorm, along with the Pen-Link platform which Oakland County purchased at the same time as Hailstorm, is the most powerful surveillance technology available to law enforcement today. Hailstorm was used by the military in the Iraqi war, among other things to coordinate drone attacks.

Though it’s full capabilities have been kept very hush-hush, Hailstorm reportedly enables the operator to locate, collect data (including content), and even download Trojans onto cellphones garnering full access and even complete control of the cellphone to the attacker. But we’re expected to believe the Sheriff when he states that Hailstorm doesn’t do the very thing it was designed to do (for the military), and that Oakland County shelled out the extra cash for the most overreaching surveillance capabilities available while not actually using them.

These are only a few examples of the IMSI catchers in use by law enforcement. There are many others, including some available online to anyone. They can be operated secretly by anyone with the means to do so, and law enforcement is no longer alone in their interests of exploiting our cellular network vulnerabilities.

Anyone with $2000 to spend can purchase or build an IMSI catcher to monitor all of your cellular transmissions by exploiting vulnerabilities that could be easily fixed, but instead are left in place to help facilitate government surveillance.

Last week’s change in DOJ policy which now requires that federal agents secure a warrant and delete all non-target data daily is long overdue, but it’s not legally binding at the state or local level. It’s unclear whether law enforcement in Michigan believes they need a warrant or simply a Pen/Trap order to deploy an IMSI catcher.

According to Sheriff Bouchard and McCabe they require a warrant to use Hailstorm, but they also claim it’s not a surveillance device, so with no oversight it truly remains unclear. It appears there are legal grounds to argue that a warrant should be required, particularly depending upon where the individual is when the surveillance takes place. We can’t reasonably be expected to believe that we voluntarily give up the right to privacy simply by using a cell phone.

The continued roués of secrecy protecting law enforcement from exposing their overreach of unchecked power with military grade surveillance equipment, and their likelihood of inevitable violations of our Fourth Amendment and other Constitutional rights based on the very nature of this technology, needs to be addressed here in Michigan.

Hopefully someone resurrects the Hailstorm bills HB 5710 and HB 5712 which would require law enforcement to secure a warrant prior to use of this type of surveillance, inform innocent citizens when their data has inadvertently been collected, create penalties for misuse, as well as create a much needed oversight committee to ensure these devices are being used lawfully. It’s that or succumb to Sheriff Bouchard’s Jedi mind tricks when he essentially states that “these are not the droids you’re looking for”.

Interestingly enough, anyone with an Android phone can download a number of apps that identify IMSI catchers. These apps will alert a person when they might be connected to an IMSI catcher. Unfortunately, no such technology is available for iPhones.

There is however a free app for iPhones that allows end-to-end encryption of calls and texts. There are also a number of other types of cellular communications encryption that can help prevent a person from being as easily vulnerable to intrusive surveillance from criminals and the government alike. Many more than are listed here. If you’re at all concerned about the privacy of your communications adding additional layers of encryption is worth looking into, and if you live in Oakland County get rid of your iPhone and buy an Android.

Legal Implications of Cellular Surveillance

The previous article on Cellular Surveillance outlined the overall gist of the rampant deceit and the shroud of supposed secrecy cloaking law enforcement’s use of IMSI catchers.

Here we’ll examine some of the specific ways in which IMSI catchers can be used, the potential differences in legal implications of the way in which they’re used, and highlight some of the ways citizens can protect themselves from this type of surveillance.

Pen/Trap Order vs Warrant

A great deal of controversy surrounds the varying opinions from one jurisdiction to another about the legal steps needed to be taken by law enforcement to deploy an IMSI catcher. Some agencies have used IMSI catchers without any warrants or court orders whatsoever, others require filing for a Pen/Trap order, some hybrid orders, and some jurisdictions require a warrant.

The majority of state and local agencies, as well as federal agencies up until last week, only require that a Pen/Trap order be issued from a court in order to deploy IMSI catchers. One problem with this is that the Pen/Trap Statute was crafted to allow solely for the recording of incoming and outgoing numbers, and IMSI catchers are capable of much greater degrees of surveillance at the operator’s discretion.

Additionally, the legal threshold for issuing a Pen/Trap order is very low. In fact all that is required is for law enforcement is to state that “the information likely to be obtained is relevant to an ongoing investigation.” 18 U.S.C. § 3122(b)(2).

Passive vs Active Monitoring

IMSI catchers can be used passively or actively.

Passive monitoring exploits the lack of, or limited level of encryption used to transmit data from a cellphone to a cell tower. Passive monitoring collects the transmissions between a cellphone and cell tower without interfering with them, and then decrypts that transmission in real-time for analysis. The type of data collected from passive monitoring is limited to meta-data like location and incoming/outgoing numbers.

Active monitoring exploits another well-known vulnerability; the lack of authentication required by cellphones to validate cell towers. Active monitoring actually simulates a cell tower tricking cellphones into connecting to the IMSI catcher.

IMSI catchers can then launch “man in the middle attacks” actively posing as the carrier network, or the target cellphone, effectively controlling all incoming and outgoing transmissions. They can be used to identify cellphones within their vicinity whether they’re in use or not, intercept incoming and outgoing calls and texts, and initiate denial of service attacks blocking cell phone service.

The newest breed of IMSI catchers like the Hailstorm which was recently purchased in Oakland County can even download Trojans to a cellphone gaining complete control over it. It should be noted that Stingrays, which are the most common IMSI catcher used across the country, can do the same with the use of additional programs being run by the operator. All virtually without anyone knowing they’ve done so.

Both types of surveillance have some common characteristics: both methods can be performed with IMSI catchers, both exploit well-known vulnerabilities in our cellular networks, both are indiscriminate by their very nature performing dragnet like surveillance of entire areas, and unlike carrier-assisted surveillance both are often deployed without any warrants or court orders.

Though IMSI catchers have the capability to perform passive or active surveillance the distinction between the two may be important due to the varying interpretations of legal requirements needed to deploy IMSI catchers in either mode.

To make matters more confusing these interpretations vary from one jurisdiction to another. Additionally, it’s important to note that once law enforcement has an IMSI catcher like the Hailstorm, or Stingray, the type of capabilities and in turn the type of surveillance deployed is entirely in the hands of the operator.

There’s absolutely nothing stopping an operator of a Hailstorm who may have a court order to collect meta-data from simply flipping a switch and actively monitoring voice, text, and data content, or even gaining access and complete control of a cell phone.

Much of the problem is that our state and federal government have yet to draft appropriate legislation dealing with this highly invasive technology. The inadequacy of our current statutes to contend with this technology was first pointed out by a Federal Magistrate Judge 1995, but rather than address the concerns the “all you can eat surveillance buffet” was offered to law enforcement as they were coached how to keep it all very hush-hush.

The 1995 Digital Analyzer Magistrate Opinion

In 1995 a Federal Magistrate Judge issued the first legal opinion of the government’s application of digital analyzers (IMSI catchers used passively). In this case the government wanted to “analyze signals emitting from any cellular phone used by any one of five named suspects of a criminal investigation”.

At that point DOJ policy was presumed to be to file for a pen register order authorizing surveillance which the government was doing. Magistrate Judged Edwards denied the government’s application explaining that a Pen/Trap order wasn’t required because the statute limits its application to “a device which records or decodes electronic or other impulses which identify the numbers dialed or otherwise transmitted on the telephone line to which such a device is attached”. He explained that since this technology isn’t intended to be attached to the device that the Pen/Trap statute isn’t applicable.

Judge Edwards further stated that based on Smith v. Maryland that the government’s use of digital analyzers for location data and real-time collection of incoming and outgoing telephone numbers doesn’t constitute a search or raise any Fourth Amendment concerns. His basis was that telephone users willfully provide the numbers they dial to a third party the “numbers dialed by a telephone are not the subject of a reasonable expectation of privacy” and “no logical distinction is seen between telephone numbers called and a party’s own telephone number, device number, or serial number, all of which are regularly voluntarily exposed and known to others”.

While Judge Edwards asserted that current Pen/Trap statutes don’t expressly permit or prohibit the use of digital analyzers he personally expressed strong concerns regarding their use in law enforcement, particularly for the privacy rights of innocent third parties within the vicinity of these devices, the lack of congressional oversight, as well as the lack of required recordkeeping and in turn accountability.

So while the court couldn’t prevent the government from utilizing these technologies by law it was rightly concerned by the implications of the decision. Ultimately, this decision has in part resulted in an absolute surveillance free for all with indiscriminate Fourth Amendment violations rivaled only by the NSA surveillance revealed by Edward Snowden.

The difference is this surveillance isn’t limited to the federal government. At this point it’s not even limited to state and local law enforcement.

DOJ Policy

Up until last week DOJ policy towards IMSI catchers has been convoluted, self-contradictory, and like other law enforcement at times outright misleading to the courts and general public.

Based on Judge Edwards’s 1995 opinion the DOJ published a document in 1997 wherein they stated that provided law enforcement doesn’t intercept communications data, and they don’t require carrier-assistance, no warrants are required for the passive or active use of IMSI catchers. In the same document they stated that while agencies weren’t required by law to do so that they should probably continue to file for Pen/Trap court orders anyway when utilizing IMSI catchers for Pen/Trap purposes. So they clearly point out the loophole in the law while mentioning that prosecutors probably shouldn’t jump through it.

Surprisingly enough in 2001 the Patriot Act broadened the Pen/Trap statute by adding the term “signaling information” to the definition of pen register which was previously limited to “numbers dialed or otherwise transmitted”. Based on the new legal definition the 2005 Electronic Surveillance Manual published by the DOJ advises prosecutors that the new pen register definition “encompasses all of the non-content data between a cellphone and a provider’s tower.” While they pointed out this change they never officially state whether passive surveillance breached any Fourth Amendment limitations which would legally require securing a pen register, or whether it was simply a best practice for any IMSI catcher deployment. The fact that programs in 2007 started in which US Marshals began operating IMSI catchers from planes flying over cities collecting data on tens of thousands of people at a time might give us some insight.

The legal grounds for deploying IMSI catchers became even shakier after the 2012 Cellphone Simulator (Stingray) Magistrate Opinion was published.

Operating under the policy of filing for Pen/Trap orders for deployment of the active use of a Stingray device the government sought an order in which was ultimately denied by Magistrate Judge Owsley in Texas. Judge Owsley cited a lack of represented understanding of this technology on the part of the law enforcement and prosecutors involved, as well as a definitional concern whereby he stated the need for a known telephone, or other identifying number in order to issue a Pen/Trap order.

Based on the fact that the government did not have that information and indeed anticipated identifying that specific information through the use of the Stingray monitoring all cellular transmissions within the vicinity the targets were expected to be, Judge Owsley denied the application. He further expressed concerns regarding a lack of explanation for what would happen with the data collected from innocent cellphone users in the areas these Stingrays are deployed. Based on this opinion federal law enforcement would now first have to identify specific telephone or other identifying numbers prior to seeking a Pen/Trap order, at least for active surveillance. This legal opinion likely led to their lack of desire to clearly and officially state their policy towards IMSI catchers until last week.

A welcomed, while albeit systemically limited policy change was announce to take effect immediately last week on the part of the DOJ in regards to cell site simulators (IMSI catchers).

The new policy requires all federal agents to secure an actual warrant to deploy IMSI catchers. This certainly sets a more appropriate legal threshold for issuance than Pen/Trap orders for these highly invasive technologies with capabilities exceeding what Pen/Trap statutes were intended to encompass. This new policy also supposedly prevents the surveillance of content including conversations, text, data, as well as stored data on the phone. How exactly this might be enforced when nothing is stopping the operators of these devices from using them however they please is not mentioned. No penalties are put in place for misuse. Additionally, this new policy mandates that federal agents delete captured data from non-targeted individuals daily. While this policy change is a step forward in protecting our Fourth Amendment rights from the federal government, it doesn’t change the way state and local agencies will use these technologies.

Since the cat is already out of the bag some have the wonder if this policy change is too little too late.

State and Local Use

This suggested policy change from the DOJ is not legally binding for state or local law enforcement who have been documented in many cases to be deploying IMSI catchers passively and actively without any types of warrants for years.

So we’ve provided law enforcement with the equipment to enable surveillance without anyone other than the operators knowing they’ve done so, while hoping that they’ll resist temptation knowing there’s no oversight. This temptation has been too much to bear for many agencies here in Michigan

Secret Stingray

The government considers their use of this technology to be “law enforcement sensitive information”, and they’ve gone to great lengths to protect the shroud of secrecy.

It was only after a decade after their initial use that a Stingray came up in a pretrial case against Daniel Rigmaiden who was charged with fraudulently collecting hundreds of tax returns from deceased and other third parties. The government identified an IP address associated with a prepaid data-card used to file the tax returns, collected cellular tower history data from the carrier to identify the location of its use within a quarter square mile, and used the Stingray to track it to Rigmaiden’s apartment where it was plugged into his computer.

Prior to his arrest the government didn’t know Rigmaiden’s identity. Before locating the data-card with the Stingray the government obtained a search warrant pursuant to Fed. R. Crim. P. 41(b) authorizing the use of a cell site simulator.

By Joe Stone

Suggested reading for more in-depth analysis on IMSI catchers

STINGRAYS: The Most Common Surveillance Tool the Government Won’t Tell You About. A Guide for Criminal Defense Attorneys

Your secret stingray’s no secret anymore: The vanishing government monopoly over cell phone surveillance and its impact on national security and consumer privacy

A Lot More than a Pen Register, and Less than a Wiretap: What the Stingray Teaches Us about How Congress Should Approach the Reform of Law Enforcement Surveillance Authorities

Triggerfish, Stingrays, and Fourth Amendment Fishing Expeditions

FROM SMARTPHONES TO STINGRAYS: CAN THE FOURTH AMENDMENT KEEP UP WITH THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY?

IMSI Catchers and Mobile Security

Organizations on the frontlines with even more up to date information, including FOIA requests: EPIC, Electronic Frontier Foundation, and the ACLU.

Pell, Stephanie K., and Christopher Soghoian. “Your secret stingray’s no secret anymore: The vanishing government monopoly over cell phone surveillance and its impact on national security and consumer privacy.” Harvard Journal of Law and Technology, Forthcoming (2014).

Ooi, Joseph. “IMSI Catchers and Mobile Security.” (2015).

Owsley, Brian L. “Triggerfish, Stingrays, and Fourth Amendment Fishing Expeditions.” Hastings LJ 66 (2014): 183.

Hardman, Heath. “Brave New Wrold of Cell-Site Simulators, The.” Alb. Gov’t L. Rev. 8 (2015): 1.

Pell, Stephanie K., and Christopher Soghoian. “A Lot More than a Pen Register, and Less than a Wiretap: What the Stingray Teaches Us About How Congress Should Approach the Reform of Law Enforcement Surveillance Authorities.” (2014).

Aug 25, 2015 | Blog, News

What…You are surprised?

These days you should just assume your privacy and personal information is being monitored or hacked.

Read this article from USA Today. Read the full article with links to other very interesting and informative articles.

USA Today

BALTIMORE — The crime itself was ordinary: Someone smashed the back window of a parked car one evening and ran off with a cellphone. What was unusual was how the police hunted the thief.

Detectives did it by secretly using one of the government’s most powerful phone surveillance tools — capable of intercepting data from hundreds of people’s cellphones at a time — to track the phone, and with it their suspect, to the doorway of a public housing complex. They used it to search for a car thief, too. And a woman who made a string of harassing phone calls.

In one case after another, USA TODAY found police in Baltimore and other cities used the phone tracker, commonly known as a stingray, to locate the perpetrators of routine street crimes and frequently concealed that fact from the suspects, their lawyers and even judges. In the process, they quietly transformed a form of surveillance billed as a tool to hunt terrorists and kidnappers into a staple of everyday policing.

The suitcase-size tracking systems, which can cost as much as $400,000, allow the police to pinpoint a phone’s location within a few yards by posing as a cell tower. In the process, they can intercept information from the phones of nearly everyone else who happens to be nearby, including innocent bystanders. They do not intercept the content of any communications.

Dozens of police departments from Miami to Los Angeles own similar devices. A USA TODAY Media Network investigation identified more than 35 of them in 2013 and 2014, and the American Civil Liberties Union has found 18 more. When and how the police have used those devices is mostly a mystery, in part because the FBI swore them to secrecy.